Malaysia’s Next Mega Gamble: The High-Stakes Bet Behind Andaman Island

A new island is rising from the water off Malaysia’s northern coast, carrying a price tag of roughly 14 billion dollars. On the surface, it looks like progress. New land. New roads. New bridges. A fresh extension of one of the country’s most important cities. Yet Malaysia has travelled this path before, and some of its most ambitious reclaimed cities now struggle with slow occupancy and uncertain futures. That history raises a question that reaches beyond engineering: Is Malaysia building its next urban success, or preparing to repeat a costly national mistake. I remember standing on Penang’s shoreline and watching dredging ships move across the horizon, and the scale of the transformation felt almost unreal.

A Coastline Reshaped by Ambition

Over the past three decades, Malaysia has steadily pushed its horizon outward. Since 1991, the country has reclaimed more than 80 square kilometres of land from the sea. That figure continues to grow as major cities respond to rising demand for housing, tourism, and industry. These new shorelines stretch far beyond their original boundaries, offering space for ports, marinas, high-rise neighbourhoods, and commercial corridors that the mainland can no longer support.

Malaysia is not alone in this strategy. Singapore, Hong Kong, and Dubai have built extensive reclaimed districts to overcome limited land. Yet Malaysia’s geography places unique pressure on certain regions, especially Penang, where land scarcity intersects with strong economic growth.

Penang Island stands at the centre of this story.

Also Read: Why China Is Building Ports Across the Caribbean Near the United States

Penang’s Rising Demand and Shrinking Space

Penang is one of Malaysia’s cultural and economic pillars. The state attracts millions of visitors every year and serves as a major technology hub, drawing companies like Intel, Micron, and AMD. George Town is known globally for its heritage streets, street food, art culture, and unique urban charm.

This international attention intensified after George Town earned UNESCO World Heritage status in 2008. Tourism surged. Property values climbed. Investors began turning older neighbourhoods into boutique hotels and restored shophouses. The growth lifted the economy but also squeezed local residents and placed new pressure on land.

Penang’s geography limits what can be built inland. The island contains steep hills, dense forests, and environmentally sensitive areas that cannot be developed. Much of the coastline already carries high-rise apartments, commercial corridors, and key transport routes. As the population grew, the city faced a clear constraint: there was no room to move inward.

This reality pushed Penang to look outward into the sea.

The Birth of Andaman Island

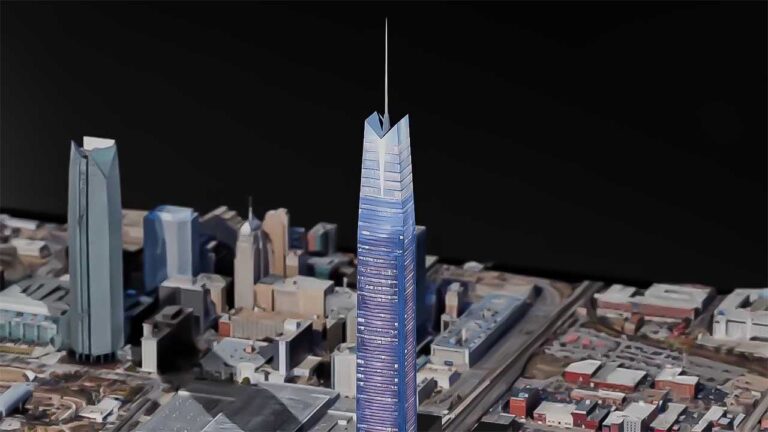

The search for new space led directly to Andaman Island, a 760-acre man-made island rising just off Penang’s northern waterfront. Unlike Malaysia’s past megaprojects, Andaman is not treated as an independent city. It is designed as a seamless addition to Penang’s urban fabric, with roads, utilities, drainage systems, and public spaces extending naturally from the existing city.

The project forms part of a larger masterplan known as the Gurney Waterfront and Seri Tanjung Pinang Phase 2 redevelopment. Approved in stages from the mid-2010s onward, the plan aims to reshape Penang’s northern shoreline by the end of this decade.

Satellite images reveal how quickly the landscape changed. What was open sea in 2016 now carries entire neighbourhood blocks, construction yards, cranes, and early high-rise structures. The island’s development schedule stretches through the late 2020s, with housing, parks, and commercial spaces planned in phases to match market demand.

This controlled growth model contrasts sharply with Malaysia’s past megaprojects, where supply often outpaced reality.

The Science Behind Lifting Land From the Sea

Creating stable land from offshore waters demands precision. The process begins several kilometres away, where dredging ships extract sand from approved seabed zones. This sand is pumped to the project site through reinforced steel pipelines. Over time, layer upon layer raises the seabed until new land emerges above the waterline.

Yet the visible surface is only the start. Beneath the sand lies soft marine clay that cannot support buildings on its own. Engineers address this through a detailed settlement strategy:

• Thousands of vertical drains are inserted deep into the soil.

• These drains guide trapped water upward.

• Heavy sand surcharges compress the land, forcing water out and strengthening the ground.

This settlement process can take years, but skipping it would risk structural instability. Studies published by Malaysia’s Public Works Department show that poorly settled reclaimed ground can sink by tens of centimetres per year, damaging roads and foundations.

When the land stabilizes, engineers strengthen the edges. Around Andaman, workers installed a thick ring of rock revetments, each stone weighing more than 100 kilograms. These sloped barriers protect the island from waves, erosion, and the long-term threat of sea-level rise. International coastal research, including findings from the United States Army Corps of Engineers, shows that sloped revetments absorb wave energy far better than vertical walls.

This investment already proved its worth in Penang. During the 2004 tsunami, areas shielded by sloped protection suffered less severe impact than those behind rigid structures.

Once the land is settled and secured, construction can begin.

Connecting the Island to Penang’s Urban Life

Land is only useful when it connects to the city that depends on it. Andaman Island includes two planned bridges linking it to key parts of Penang’s northern coastline. One ties directly into Straits Quay, a marina district that is itself built on reclaimed land. The second connects to Gurney Bay, a major waterfront park and commercial redevelopment scheduled to open in phases through 2025.

These connections matter. Without them, Andaman risks becoming a quiet offshore enclave. With them, it becomes a natural extension of Penang’s daily life.

Why Penang Wants This Island

Housing demand is a major driver. In Penang, coastal homes command a premium of up to 50 percent over inland units. Buyers value sea views, walkable waterfront districts, and access to lifestyle amenities.

Andaman Island aims to deliver around 5,000 homes for approximately 16,000 residents. Early towers have already reported strong sales, according to developer E&O’s public financial statements. Prices on the island start around 120,000 dollars and rise to more than 1.6 million dollars for luxury units.

This aligns with Penang’s existing market demand, unlike previous megaprojects that struggled to find buyers.

Learning From Malaysia’s Most Famous Reclaimed Failure

No discussion about Malaysian reclamation can avoid Forest City. This 100-billion-dollar development was meant to house 700,000 people across four artificial islands in Johor. The vision was vast. The engineering was impressive. Yet demand never materialized.

Several forces aligned against it:

• China’s property slowdown reduced overseas investment.

• Malaysian policy shifts limited foreign residency.

• Global travel collapsed during the pandemic.

• Market expectations failed to match actual local demand.

By 2023, investigative reports from outlets like Bloomberg and Al Jazeera estimated occupancy at around one percent. Thousands of finished units remain empty.

The contrast with Andaman is clear. Andaman targets a local demand base, sits beside an already dense city, and grows in controlled phases rather than giant leaps.

Still, no reclaimed project is free from risk.

Also Read: China’s $70 Billion Water Project That Reversed an Entire River

A Future Built on More Than Sand

Andaman Island could become an example of smart coastal expansion, strengthening Penang’s economy and easing its space constraints. Or it could follow the softer trajectory of other reclamation projects that delivered beautiful districts but struggled with long-term occupancy.

Success depends on real demand, fair pricing, infrastructure reliability, and the ability to integrate new communities with existing life on Penang Island. The project’s scale gives it a better chance of success, but time will judge how well its lessons were applied.

Andaman is a reminder that megaprojects involve more than concrete and engineering. They reveal a country’s ambitions, risks, and willingness to reshape its coastline in search of a future that no longer fits on the land it started with.