Inside the Maldives’ $10 Billion Floating City Megaproject

The Maldives rises from the Indian Ocean like a fragile necklace of coral. More than 1,200 islands scatter across turquoise lagoons, shaping one of the most recognizable landscapes on Earth. I stood on a shoreline here and felt both wonder and unease. The sand felt soft under my feet, yet the ocean pressed close, reminding me how narrow the margin between survival and loss has become. This nation holds the world’s lowest average elevation, sitting barely 1.5 meters above sea level. Rising oceans no longer feel like an abstract future threat. You can see erosion steal beaches season by season. You can watch saltwater creep into freshwater lenses beneath the islands.

Sea levels in the Indian Ocean continue to rise at roughly 3.9 millimeters per year, a pace higher than the global average reported by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate models project that by mid-century, large sections of the Maldives could face chronic flooding. Storm surges already overwhelm existing sea defenses during heavy monsoon seasons. This reality drives one urgent question across the archipelago. Can engineering protect an entire country that floats at the edge of disappearance.

The Pressure on a Nation at the Waterline

Daily life in the Maldives tells a stark story. Malé, the capital city, ranks among the most densely populated places on Earth. Over 230,000 residents share an island measuring about 5.8 square kilometers. Apartment blocks stack against the shoreline. Water desalination units work around the clock. Power cables and drainage systems operate at near-maximum limits. Each new family strains infrastructure designed for far fewer people.

The government channels nearly a third of national spending into coastal protection and land reclamation. Engineers build concrete seawalls that ring islands like rigid collars. Projects pump sand from deep lagoons to expand shorelines, creating raised plateaus of newly formed land. Hulhumalé, the nation’s largest reclaimed island, already houses more than 60,000 residents and still grows upward and outward. None of these measures solve the underlying challenge of long-term elevation loss. Sea defenses require constant maintenance. Reclaimed land demands continuous reinforcement. Coral reef degradation removes the islands’ natural barriers against waves.

Coral bleaching events linked to warming waters decimated reef systems around several atolls. Scientists from the Maldives Marine Research Institute estimate that some reefs lost more than 60 percent of their living coral cover since the major 2016 bleaching event. Weaker reefs mean weaker wave protection. Eroded ecosystems push communities closer to the open ocean. I watched fishermen tie boats higher on beaches because tides ride farther upshore than before.

Also Read: D.C. Spent $500 Million to Save Its Teams… But At What Cost?

The Birth of Floating Urbanism

Faced with the limits of reclaiming land from the sea, Maldivian leaders turned to a daring alternative. They approved the Maldives Floating City project in 2021, marking the first attempt to create a large-scale ocean-based urban district designed to host permanent residents. Instead of pushing back the water, planners chose to live on it.

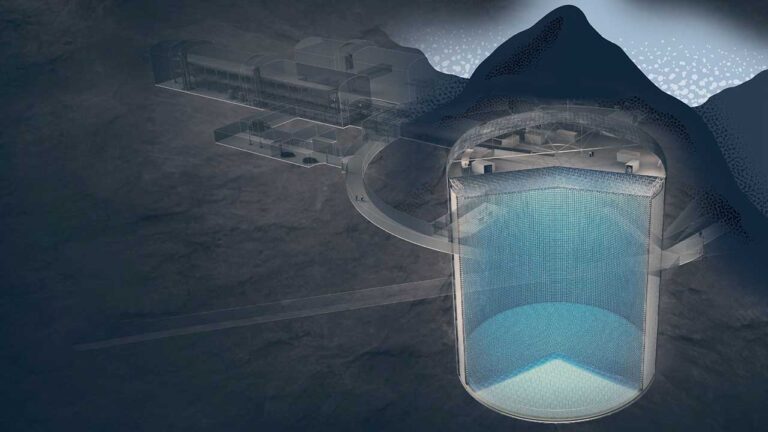

The vision centers around a settlement of roughly 5,000 residences, complemented by hotels, retail blocks, medical clinics, schools, public waterfront parks, a mosque, sports facilities, and community centers. Designers arranged platforms in interlocking hexagonal shapes inspired by brain coral patterns native to local reefs. This geometry allows discrete modules to flex independently during waves and reduces structural stress.

Roadways span more than sixteen kilometers across the floating matrix, though motor vehicles remain restricted. You travel the city by bicycle, on foot, or using battery-operated buggies. This approach limits emissions and preserves the quiet rhythm of lagoon life. Each residential unit connects directly to water access points, allowing boats to function as everyday transport.

Engineering Designed to Move with the Ocean

Construction relies on buoyant concrete pontoons anchored to the seabed using flexible mooring systems developed by Dutch marine engineering firm Docklands. These anchors secure platforms against drift but permit vertical movement during tides. Engineers tested prototypes under simulated cyclonic loads equivalent to regional storm forces exceeding 160 kilometers per hour. Each module carries storm management channels that divert wave energy and reduce platform uplift pressure.

Modular construction enables controlled expansion. Crews fabricate housing units offsite, then tow completed segments into position for anchoring. This method avoids intensive seabed dredging that normally damages reef ecosystems. Engineers maintain open water circulation beneath the platforms to prevent stagnation and preserve marine oxygen levels. Sunlight filters through spaced pontoons to sustain coral growth below.

Environmental integration drives the entire design approach. Artificial reef blocks installed beneath sections of the city support fish nurseries and coral transplantation programs under supervision of the Maldives Marine Research Institute and international conservation partners. Marine biologists monitor water quality continuously for changes in salinity, temperature, and phytoplankton levels.

Homes draw power from rooftop solar arrays feeding floating microgrids. Battery storage systems provide energy persistence throughout cloud cover and nighttime demand peaks. Desalination units produce freshwater locally. Greywater recycling plants treat wastewater onsite for landscape irrigation and non-potable reuse. Designers configured emergency shelters into elevated platforms capable of accommodating residents during major storms.

Former Maldivian President Mohamed Nasheed championed the concept publicly as both a national safeguard and a model for other coastal nations. He described floating development as a path toward climate security that does not sacrifice territory or cultural identity. Docklands brought direct experience from the Netherlands, where floating neighborhoods such as IJburg already operate successfully within flood-prone environments.

Financial Reality and Delayed Timelines

The government introduced the floating city with a projected investment of roughly $10 billion. Public financing mixes with private foreign capital from Asia and Europe. Condo pre-sales target international buyers seeking climate-resilient property holdings and vacation homes. Locals receive guaranteed allocation quotas for select housing tiers supported through subsidized financing programs.

Despite early momentum, construction pace slowed. Global material price spikes following pandemic disruptions and supply chain instability delayed pontoon fabrication and mooring deliveries. As of early 2025, several residential clusters remain under early assembly phases rather than full habitation. The original target for major occupancy in 2027 now appears optimistic.

Transport logistics also challenge timelines. Crews must ship massive floating modules into narrow lagoons while maintaining delicate coral exclusion zones. Skilled marine engineers require rotational deployment schedules that safety protocols frequently interrupt during monsoon seasons.

Yet global attention remains intense. Architectural institutes, climate research centers, and engineering forums still cite Malé Floating City as the most ambitious permanent floating settlement proposal currently under active development worldwide.

The Parallel Rise of an Offshore Financial Hub

Beyond maritime housing, the Maldives seeks economic insulation from tourism volatility. The government approved development of the Maldives International Financial Centre at Hulhumalé with an investment exceeding $8.8 billion. The district will operate as a zero-tax offshore banking and technology hub supporting corporate finance, asset management, blockchain firms, and cryptocurrency exchanges.

Plans include three iconic high-rise towers, conference halls, retail districts, schools, museums, green waterfront parks, and nearly 6,000 residential units. Crews reclaim additional land elevated several meters above present sea levels and protect zones with reinforced storm-surge barriers. Developers expect the complex to contribute nearly $1 billion annually to national gross domestic product once full operations begin around 2030.

Energy systems integrate solar, coastal wind capture, and hybrid marine power storage systems similar to those deployed across Southeast Asian island microgrids. Flood-resistant foundations and elevated podium decks protect building cores against extreme storm surges modeled on projections through 2100.

Rebuilding Connectivity Across the Atolls

Infrastructure investments extend beyond megastructures. The Sinamalé Bridge, operational since 2018, links Malé to Velana International Airport. Commutes that once required ferry schedules now take roughly five minutes by road. Passenger flow grew faster than anticipated, pushing adjacent island development forward.

The Thilamalé Bridge now under construction stretches six kilometers, connecting Malé with Hulhumalé Phase II and Gulhifalhu. Project costs exceed $500 million and involve marine pylons engineered to withstand powerful seasonal currents. Completion remains expected by late 2026.

Southern atolls also benefit. Bridge networks in Addu City link islands that previously depended on limited ferry crossings, enabling direct ambulance transport, school commutes, and freight logistics. For a dispersed island nation, these connections reshape daily life as profoundly as airports or ports.

Tourism Keeps Expanding

Tourism still underwrites national revenue. High-profile resorts extend across remote atolls with integrated seaplane terminals, underwater restaurants, suspended villas, and advanced sustainability systems. The Zamani Islands Resort expects completion in 2026 with a superyacht marina and coral conservation research labs woven into guest programs. The $600 million Samana Ocean Views project remains slated for phased openings through 2029.

Velana International Airport’s $1 billion expansion completes in 2025. New runways and terminal facilities raise annual capacity to over 7 million passengers and position the Maldives to handle continuing growth. Elevated terminal structures account for projected flooding risks using reinforced grade platforms and sealed utility corridors.

Also Read: Is the Eiffel Tower Falling Apart? The Hidden Battle Against Rust

Engineering Against an Unrelenting Ocean

Every project shares one constant pressure. The sea never stops rising. The scale of investment required to sustain these defenses remains enormous. Artificial islands require replenishment cycles. Floating systems need constant inspection of corrosion-resistant mooring assemblies. Solar grids face exposure to saline humidity that shortens equipment lifespan.

Environmental monitoring continues to improve but uncertainty remains. Artificial reefs may support marine populations, though ecological balance can shift in unpredictable ways. Coastal development increases vessel traffic that risks coral anchoring scars and sediment disruption. Social inequality also challenges long-term success. Property pricing tied to overseas investors places housing beyond reach for most Maldivians without government subsidies.

A Nation Building at the Edge

The Maldives now stands as a proving ground for climate engineering. Floating neighborhoods, ambitious financial districts, new transportation bridges, and resort expansions all reveal a single national strategy. Build upward. Build outward. Build afloat.

No country faces disappearance with quite the same immediacy. These projects aim not at luxury alone but at survival. They buy time against an accelerating ocean. They test technology under real-world pressure. They ask whether humans can coexist with rising seas instead of retreating from them.

As I left the shoreline that evening, waves lapped close to the seawall beneath fading sunlight. The city behind me buzzed with construction cranes and ferry engines. The sea in front of me stretched endlessly toward the horizon. I felt the tension between human ambition and nature’s scale in every breath of warm salt air.