Why Saudi Arabia’s $3 Trillion Vision May Never Come True

In 2016, Saudi Arabia unveiled a future no one saw coming. A city stretching 170 kilometers through the desert. A floating industrial port shaped like an octagon. A winter wonderland built where snow barely falls. Branded as Vision 2030, this $3 trillion master plan aimed to transform a fossil-fuel empire into a global force in tech, tourism, and innovation. It wasn’t just urban planning. It was a complete national reinvention.

But less than a decade later, the dream looks less like the future and more like a mirage. The flagship project has shrunk. The budget has exploded. The timelines keep shifting. And the promises now clash with reality.

I’ve stood in desert regions where these mega-cities are supposed to rise, and what struck me wasn’t the grandeur it was the emptiness.

Why Vision 2030 Exists: The Oil Time Bomb

Saudi Arabia’s wealth was born from a single moment when oil was struck in Dhahran in 1938. That discovery turned a tribal monarchy into a powerhouse. Oil revenues paid for everything: roads, hospitals, education, and subsidies that allowed citizens to live without taxes.

But by 2016, that model was collapsing. Global oil demand had begun to plateau. Climate change policy, electric cars, and green energy threatened the kingdom’s main source of income. Oil still accounted for over 80 percent of export earnings, and over 40 percent of government revenue depended on it.

Vision 2030 was designed as a lifeline. Use oil wealth now, while it’s still flowing, to fund an economy that can survive without it. The plan called for diversification banking, biotech, entertainment, artificial intelligence, and tourism.

But transitions of this scale require more than slogans. They need infrastructure, human capital, international trust, and consistent execution. So far, all four are in short supply.

NEOM and the Myth of “The Line”

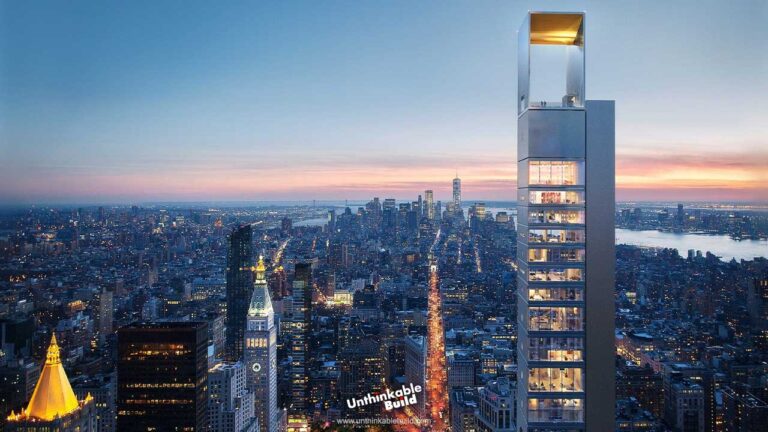

The centerpiece of Vision 2030 is NEOM a mega-city promised to span 26,500 square kilometers, about the size of Albania. At the heart of NEOM lies The Line, a 170-kilometer city designed to be car-free, emissions-free, and powered by artificial intelligence.

On paper, it looks like the future. In reality, it’s barely out of the ground. As of 2024, only 2.4 kilometers of The Line are under construction, with satellite images revealing more dust than development. Early targets promised housing for 9 million people. That number has now dropped below 300,000 and even that’s optimistic.

Then there’s Oxagon, NEOM’s floating industrial port city, still existing entirely in renders. Trojena, the proposed mountain ski resort, sits in a region that hasn’t seen consistent snowfall in over a decade. Climate data shows the average winter temperatures there rarely drop below freezing.

Other high-profile developments include Diriyah Gate, a luxury heritage project near Riyadh, and The Red Sea Project, a network of ultra-exclusive island resorts with private beaches, coral reef spas, and price tags that would exclude all but the wealthiest tourists.

Each announcement was massive. Each follow-through? Minimal. Delays, shrinking scopes, shifting contractors, and revised goals now define the landscape.

Where’s the Money Going?

Vision 2030 was always ambitious, but its financial footprint is now staggering. The original budget for NEOM was around $500 billion. Today, it has ballooned to $8.8 trillion across all projects a figure greater than the combined GDPs of India and Brazil.

The Saudi Public Investment Fund (PIF) is covering most of the cost. Once focused on diversified global investments from Uber to Blackstone it’s now overexposed to domestic real estate, hospitality, and infrastructure that won’t deliver returns for decades, if ever.

One example: a reported $40 million was spent on a single launch party for the Red Sea Project, complete with imported yachts, temporary stages, and celebrity guests. That island still has no functioning resort.

Tourism revenue projections assume 70 million annual visitors by 2030. But that’s nearly double Japan’s average without the bullet trains, centuries-old heritage, or pop culture appeal.

Even if those tourists show up and each spends $500 (a generous estimate), total income would hit $35 billion a year. That’s not even 0.5% of what Vision 2030 needs to break even.

This isn’t a funding gap. It’s an economic sinkhole.

Who Will Actually Live in These Cities?

You can pour concrete. You can build towers. But a city is only alive if people choose to live and work there.

Vision 2030 assumes an influx of 9 million skilled residents engineers, scientists, entrepreneurs, and creatives from around the world. But Saudi Arabia faces a critical challenge: global talent doesn’t move without trust.

The country’s legal system includes strict religious laws and censorship. LGBTQ+ rights are nonexistent. Journalists risk imprisonment. High-profile incidents like the killing of Jamal Khashoggi cast a long shadow over the nation’s international image.

Right now, only 2% of expats in Saudi Arabia come from Western nations. The majority are low-income workers from South Asia and Africa, many of whom are employed under the kafala system a labor sponsorship structure widely criticized for human rights abuses.

Domestically, there’s a deep reliance on government jobs. Over 75% of Saudi workers prefer the public sector due to shorter hours and better benefits. And although billions have been invested in education reform, Saudi students still rank low globally in STEM fields. Several institutions have been caught in scandals involving degree inflation and plagiarism tied to government performance metrics.

Building smart cities means building human capital. And that’s the one resource Vision 2030 can’t import at scale.

Sports and Spectacle: A Shortcut to Relevance?

When megaprojects stall, Saudi Arabia turns to spectacle.

The PIF created LIV Golf, a breakaway league that spent over $1 billion in its first year, with little viewership to show for it. The country signed Cristiano Ronaldo, Neymar, and Benzema to local football clubs, offering record-breaking contracts. Still, stadiums remain half-empty.

Concerts, esports tournaments, and international film festivals have flooded the calendar. But these efforts feel more like a checklist than a culture shift.

You can’t manufacture passion. You can’t script authenticity. Hosting Formula 1 doesn’t create grassroots motorsport fans. A Coachella-style music festival in the desert doesn’t mean the population has embraced liberal entertainment norms.

Real cultural power comes from within. And it takes decades, not dollars.

Is Vision 2030 Failing?

To be fair, some progress has been made. Non-oil sectors have grown, mostly through state-backed construction and real estate. The Saudi stock exchange has seen higher listings, and regulatory reforms have improved the ease of doing business.

But the transformation promised in 2016 hasn’t arrived. Saudi Arabia is not yet a global hub for artificial intelligence, finance, or biotech. NEOM doesn’t rival Dubai. Riyadh isn’t competing with London or Singapore. And the country’s sovereign wealth fund is becoming less liquid by the year.

If current trends continue, the risk isn’t just project delays. The kingdom could enter the next decade with half-built cities, unfilled hotels, and a generation of young Saudis left without the skills or jobs they were promised.

Final Thought: The Danger of Trying to Outrun Reality

Vision 2030 was a bold move. Few nations have ever tried to reinvent themselves so completely. The ambition itself deserves respect.

But ambition without alignment between money, manpower, policy, and time leads to collapse. And right now, Saudi Arabia is racing against the clock, building a post-oil economy with oil money and borrowed time.

You can’t escape a sunset by painting the sky. You have to accept it, plan for it, and work in the dark until morning comes.