The Panama Canal: End of an Era

Imagine a really long line of ships, and this line could affect our daily lives in a big way. Over the past few weeks, hundreds of big container ships have gotten stuck in one of the most important places for world trade, the Panama Canal.

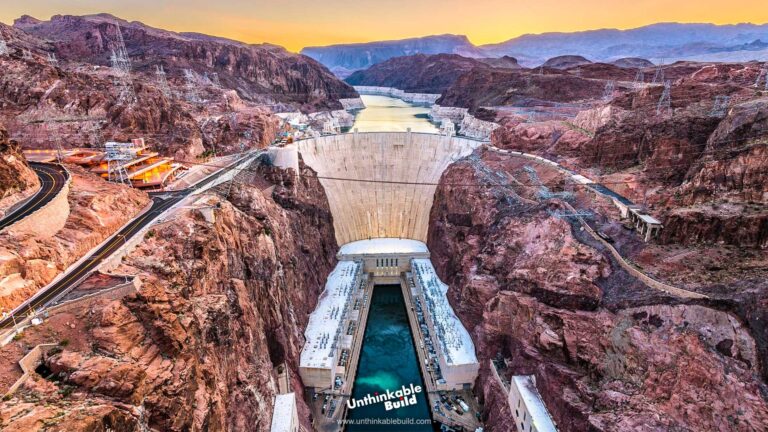

The Panama Canal is like a super-long road made of water that stretches for 80 kilometers, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. These container ships have taken over this waterway, and they’re all waiting to go through this old passage that’s been around for 100 years.

Every year, about 14,000 ships use this route, and that’s like 6% of all the things traded in the whole world! It’s like a super important road that helps stuff get to stores everywhere.

But there are some big problems now. The Panama Canal is facing problems like things breaking down, not having enough space for all the ships, and issues related to the changing climate. These problems are not going away, and they’re putting this amazing engineering wonder at risk.

In a surprising twist, our journey into the heart of the Panama Canal begins not in Panama, but in France, at the end of the 19th century. Our protagonist is Ferdinand de Lesseps, a diplomat nicknamed the Great Frenchman, who, in 1880, founded the Universal Company of the Panama Interoceanic Canal. His ambitious goal was to connect the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans by piercing through an 80-kilometer strip of land in Panama, between the Caribbean Sea and Panama Bay.

De Lesseps was no stranger to grand engineering projects; he had successfully promoted the Suez Canal, which opened a decade earlier. Buoyed by his past success, he bought the concession to the land from the United States of Colombia in 1882 and commenced work. However, challenges quickly emerged. Unlike the Suez project, the Panama Canal’s construction site was vastly different, with dense jungles and a nearly 100-meter-high hill above sea level to conquer.

The workers also faced unbearable climatic conditions, including tropical storms, mudslides, and rampant diseases like malaria and yellow fever. As problems mounted, the project teetered on the edge of bankruptcy. Attempts were made to change the plans to build a lock canal, as suggested by several stakeholders, including Gustave Eiffel, the future designer of the iconic Eiffel Tower. However, these changes came too late and coincided with a major financial scandal in France.

Also Read: Gordie Howe International Bridge Longest Cable-Stayed Bridge in North America

Tens of thousands of investors had financed the project through a massive public subscription, but much of this money ended up being used for bribing public officials rather than financing the increasingly doubtful canal. In 1889, Ferdinand de Lesseps’ company went bankrupt, costing not only the investors but also the lives of over 20,000 workers.

Despite this colossal failure, the dream of the Panama Canal persisted. The route had long been coveted, dating back to the Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century. The reason was clear: a canal of less than 100 kilometers would eliminate the need to circumnavigate the entirety of South America, saving valuable time and money.

In 1903, with the support of the United States, Panama declared its independence, which in turn granted the United States a perpetual concession for the canal and a 16-kilometer-wide strip of land across the country. Construction resumed in 1904, with engineers opting for a lock canal design. The arrival of vaccines helped control tropical diseases, making progress possible.

This monumental project spanned a decade and involved complex steam engines and innovative railway engineering. One remarkable feat was the removal of millions of tons of rock during the canal’s excavation. At its peak, nearly 40,000 workers were employed. The project cost the United States nearly $375 million, making it the most expensive venture in the country at the time.

The canal itself stretched 79.6 kilometers, featuring two artificial lakes and three massive locks, each 33 meters wide, allowing ships to cross the American continent—a monumental achievement. Tragically, an additional 5,000 workers lost their lives during the canal’s construction.

On April 15th, 1914, the Panama Canal was officially opened, just as Europe was plunged into World War I. The United States had complete control over this vital maritime route, determining the lock’s size, which was 320 meters long and 33 meters wide. These dimensions would go on to set the standard for the new generation of giant ships known as Panamax, measuring 32 meters wide and 294 meters long.

It wasn’t until the 1970s that the process began to return the canal and the American enclave to Panama, marking the end of an era and the culmination of a remarkable journey that transformed global trade.

In 1999, Panama took ownership of the famous Panama Canal. Today, this vital waterway stands as one of the country’s most crucial economic assets, contributing significantly to its finances. In fact, the canal alone accounts for a staggering 10% of Panama’s revenue. However, all the tax revenues generated and the bustling activities along this unique corridor come at a cost.

According to the Canal Control Authority’s figures, passage fees for ships vary widely, ranging from $10,000 for the smallest vessels to a whopping $300,000 for the massive neo Panamax container ships, which measure 3.65 meters in length and can carry nearly 12,000 containers. During peak periods, prices can skyrocket even higher, with certain available slots being auctioned off to the highest bidders. In a recent example, a chemical tanker paid a staggering $2.4 million to secure passage ahead of others.

Also Read: Afghanistan’s Biggest and Most Expensive Mega Projects

This financial windfall has been a lifeline for Panama, but its sustainability is now in question as the canal faces a growing crisis. The canal operates using a system established more than a century ago, where instead of removing all the land, engineers leveled the ground and created two artificial lakes: Lake Gatun and Lake Alejuela (formerly known as Lake Maden). These lakes are replenished by inland rivers. To navigate the 28-meter elevation difference above sea level, a system of locks is employed to raise and lower boats. This engineering marvel requires locomotives on the canal’s banks to maneuver vessels from one lock to another. However, this system comes at a cost: every time a boat passes through, between 200 – 250 million liters of fresh water from the canal are lost to the ocean.

This water loss was not a significant problem when rainfall was consistent. Still, the changing climate, marked by increasingly frequent droughts, has altered the rules of the game. After experiencing droughts in 2016 and 2019, Panama faced a new episode in May, during what should have been the rainy season. The situation worsened with the arrival of the El Niño weather phenomenon, which resulted in minimal water precipitation in the region, leading to lower river and lake levels. The authorities were compelled to take precautionary measures, reducing the tonnage of boats to prevent them from grounding. Additionally, the number of container ships allowed to pass through each day was reduced from 40 to 32, causing longer queues at the canal’s entrances.

In early September, it was reported that waiting times for ships had surged from 4 days during normal times to nearly 20 days in mid-August. Unlike the Suez Canal, which uses a more efficient direct passage system, the Panama Canal relies on locks, tugs, and specially trained operators to navigate ships through this complex process. With growing demand but limited capacity, waiting times have grown substantially.

Recognizing the need for change, Panama embarked on a $6 billion expansion of the canal in 2016. The new locks were designed to accommodate 95% of the world’s ships, and Lake Gatun was deepened by 45 centimeters to enable more vessels to pass through daily. However, this colossal project failed to solve the water shortage issue, leaving Panama grappling with drought-related problems.

The authorities have already imposed restrictions on passage for the coming year, but the stakes are high. If the water situation persists, ship owners may seek alternative trade routes, including the Arctic route, as global temperatures rise and ice melts, making this northern passage more navigable during the summer months. Such a shift could have far-reaching consequences.

The drying up of the canal also affects the people of Panama. Both artificial lakes, Gatun and Alejuela, serve as a vital source of drinking water for Panama City and its suburbs, supporting over 2 million residents, nearly half of the country’s population. Recognizing the pressing need for additional water sources, the canal’s administrator, Ricaurte Vasquez, proposed creating a new water reservoir west of the canal, sourced from the Indio River. This reservoir would supply Lake Gatun through an eight-kilometer underground tunnel. However, this solution, while promising, will take time to implement, with estimates ranging from 3 months with abundant rainfall to nearly 2.5 years if drought persists.

Another potential project involves extracting water from Lake Bayano and channeling it into the sea passage. These developments, though hopeful, still require consolidation, approval, and financing before they can be realized.

In the latest update available at the time of this video’s release, the canal management company reported some improvement in ship waiting times. However, Lake Gatun’s water level remains critically low, underscoring that the problem is far from resolved. Panama faces a challenging road ahead as it strives to safeguard this iconic waterway, which not only drives its economy but also quenches the thirst of millions of its citizens.