Vietnam’s 16 Billion Dollar Mega-Airport Gamble: Inside the High-Stakes Push to Build a New Global Aviation Hub

Southeast Asia stands at a turning point in air travel. Passenger demand across the region keeps rising at a speed few predicted, lifting tourism, reshaping trade routes, and testing airports that now operate close to their physical limits. More than one hundred million international travelers pass through the region each year, and forecasts from Boeing and ICAO show traffic here could more than triple within two decades. I have watched airports across Asia fill faster than planners expected, and the urgency feels real when you see runways and terminals straining under the pressure.

Most major countries in the region responded early by expanding or rebuilding their primary airports. Vietnam waited longer, and that delay created both a challenge and an opening. Instead of expanding Ho Chi Minh City’s congested Tan Son Nhat Airport, the country committed to a far bolder move: a new mega-airport with a projected cost of up to sixteen billion dollars, built on a greenfield site miles away from the country’s economic capital. This massive project carries enormous promise and equally serious risk. Walking sites like this in the past taught me how a single airport can lift a nation’s standing or become a heavy burden when ambition outruns planning.

A Region Racing Toward the Next Great Aviation Hub

Vietnam enters an environment shaped by powerful regional competitors. Singapore is developing Terminal 5 at Changi Airport, a ten-billion-dollar expansion that will push long-term capacity toward one hundred fifty million passengers. Kuala Lumpur International Airport plans a similar ceiling. Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi Airport keeps building out terminals and runways to support more than one hundred twenty million travelers. In the Philippines, the new Bulacan International Airport rises north of Manila, designed for one hundred million passengers every year.

These projects reflect a broader push to capture transfer traffic, attract major airlines, and strengthen economic influence. Vietnam joins this race later than others, but its long-term aviation demand gives it a strong reason to leap forward.

Also Read: Inside Bhutan’s $10B Gelephu Mindfulness City: The World’s Most Unusual Urban Experiment

Why Vietnam Reached a Breaking Point

Ho Chi Minh City drives Vietnam’s economy, and its only major airport has struggled to keep pace. Tan Son Nhat handled close to forty million passengers annually even though it was originally built for far fewer. The airport sits inside a dense urban grid that blocks further expansion. Traffic congestion spills into surrounding districts. Terminal space feels tight even during off-peak hours. Airlines schedule around capacity limits rather than passenger demand.

Vietnam’s broader tourism surge adds more pressure. In the first quarter of 2025, the country recorded one of the fastest international arrival growth rates in the world. Visitor numbers rose thirty percent year-over-year, outpacing every other Asia-Pacific nation. Local carriers placed large aircraft orders, betting on a decade of strong demand. With no room left to grow in Ho Chi Minh City, the need for a new hub became undeniable.

Introducing Long Thanh International Airport

The solution is Long Thanh International Airport, a new global hub under construction about forty kilometers east of Ho Chi Minh City. The scale alone sets it apart. The site spans five thousand hectares, making it roughly four times larger than London Heathrow. Depending on final adjustments, the project’s estimated cost ranges from thirteen to sixteen billion dollars.

When fully built, Long Thanh will accommodate one hundred million passengers each year and move five million tonnes of cargo. This is not a satellite airport. Vietnam intends it to become a premier gateway capable of competing with established hubs across the region.

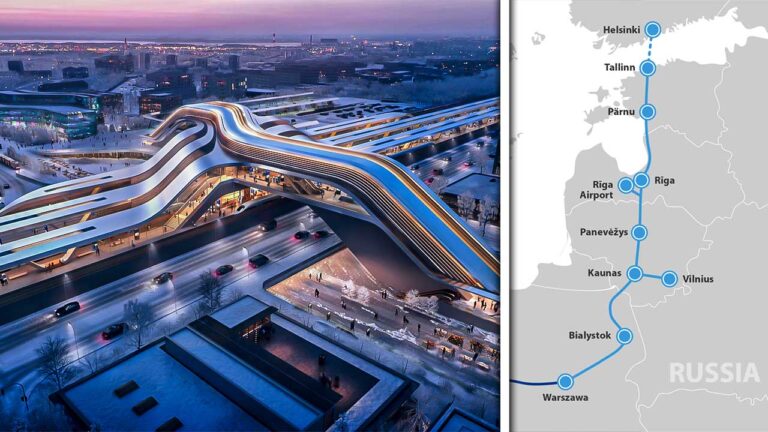

A Mega-Airport Built on a Symbolic Design

Long Thanh’s design carries national meaning. Viewed from above, the terminal layout forms the shape of a lotus, Vietnam’s national flower. The blueprint includes four major terminals paired with four long parallel runways, each stretching four thousand meters. That length supports fully loaded wide-body aircraft on long-haul routes.

Even the first phase is monumental. The initial terminal covers more than three hundred seventy thousand square meters across four levels. Above it rises an eighty-two-meter steel roof that forms one of Southeast Asia’s largest column-free indoor spaces. The visual impact alone signals Vietnam’s rising confidence. Nearby, a one hundred twenty-three-meter air traffic control tower mirrors the lotus motif, standing as both an operational structure and a national marker.

A perimeter wall more than eight kilometers long outlines the development, enclosing an area larger than many mid-sized cities.

How Long Thanh Will Expand Over Time

Vietnam chose a phased buildout to reduce financial pressure and match capacity with demand.

Phase One, budgeted at roughly four-point-six billion dollars, delivers:

- One terminal

- One four-thousand-meter runway

- Capacity for twenty-five million passengers annually

- More than one million tonnes of cargo

Phase Two adds another runway and expands terminal space significantly.

Phase Three completes the master plan with four terminals and up to six runways, allowing the airport to reach its one-hundred-million-passenger target.

This phased approach mirrors strategies used at major hubs like Incheon and Dubai, where gradual expansion supported steady growth rather than overbuilding early.

A Project Shaped by Delays and Tough Lessons

Long Thanh faced a rough beginning. Approval came just as the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted global supply chains. Labor shortages and transport delays slowed early work. Land acquisition became one of the biggest hurdles. Clearing thousands of hectares required compensation, resettlement, and coordination across multiple agencies. Mismanagement led to investigations, and several officials faced charges linked to land procedures.

The site itself added complications. Workers uncovered unexploded bombs and mines left from the Vietnam War. Each discovery forced construction teams to halt operations until explosive ordnance units neutralized the hazard. The soil also created unexpected problems. The red basalt earth produced thick dust that affected communities up to seven kilometers away. Health complaints grew until mitigation measures such as water ponds, dust barriers, and reduced vehicle speeds came online.

These setbacks reveal the complexity of building a mega-project in a fast-growing nation still managing historical, political, and logistical challenges.

Financing a Mega-Airport Without Risky Debt

One of the most important advantages Vietnam holds is the financial structure behind Long Thanh. The Airports Corporation of Vietnam, a state-owned enterprise responsible for the country’s major airports, leads the project. ACV entered the pandemic with more than one billion dollars in liquid reserves. By mid-2025, it still maintained roughly six hundred seventy-five million dollars in short-term investments.

In 2024 alone, ACV recorded more than four hundred forty million dollars in net profit. Construction spending accelerated sharply, surpassing one billion dollars between 2023 and 2024, with nearly half a billion added in the first half of 2025.

A one-point-eight-billion-dollar credit line is available, yet ACV has not drawn it. Debt levels remain stable, a sign that Vietnam has avoided the high-interest traps that burdened other infrastructure-heavy nations. This financial discipline strengthens Long Thanh’s long-term prospects.

Global Contractors Step In After Initial Bidding Failure

Vietnam first attempted to launch Long Thanh as a public-private partnership. Early bidding efforts failed because few qualified firms stepped forward under the proposed terms. In 2023, a rebid succeeded. The Vietur consortium, anchored by a major Turkish contractor with experience on large international airports, secured a contract of more than one and a half billion dollars to build the main terminal.

This step marked Vietnam’s shift toward more flexible procurement strategies. Bringing in international builders aligns Long Thanh with global standards and adds expertise that accelerates complex works.

The Critical Issue of Connectivity

A great airport cannot thrive without strong connections. Long Thanh sits forty kilometers from Ho Chi Minh City. An expressway already links the two, but rail access does not exist yet. Vietnam plans an intercity line and a metro extension, but the country’s past railway projects often progressed slowly.

If rail links lag behind the airport’s opening, travelers may rely heavily on road transport, shaping early impressions and influencing airline interest. Connectivity will determine how quickly Long Thanh can function as a true regional hub.

Will the Investment Pay Off?

Demand trends point upward. Vietnam’s aviation market now ranks among the fastest growing globally. Tourism rebounds strongly. Local airlines plan major fleet expansions. These forces give Long Thanh a strong foundation.

Still, competition across Southeast Asia remains intense. Singapore and Bangkok dominate long-haul transfers. Kuala Lumpur benefits from large land reserves and strong airline partnerships. Vietnam enters late, but its phased expansion strategy reduces exposure and increases flexibility.

Long Thanh does not need to become the region’s largest airport to succeed. Vietnam’s rising population, economic growth, and surging tourism can support multiple large hubs. The airport’s role will grow with the country itself.

Also Read: These 90-Year-Old Bridges Could Cut Off Cape Cod — Here’s the $4.5B Fix

A Defining Project for Vietnam’s Future

Long Thanh International Airport represents far more than runways and terminals. It reflects Vietnam’s infrastructure maturity, its financial discipline, and its determination to compete on a global stage. If built and connected well, the airport could elevate the nation’s position in international aviation for decades. If delays stack up or demand fails to materialize on time, Long Thanh may become one of Southeast Asia’s most debated mega-projects.

Vietnam took a bold step with this airport. The next decade will reveal whether the gamble transforms the country’s aviation future or becomes a costly symbol of ambition stretched too far.