Egypt’s $58 Billion New Administrative Capital: Ambition or Isolation?

In the heart of the Egyptian desert, a colossal city is taking shape. Not a district, not a satellite town but an entirely new capital. Just 45 kilometers east of Cairo, the New Administrative Capital (NAC) is rising from the sand. It promises Africa’s tallest skyscraper, the continent’s largest mosque, a vast Olympic-grade stadium, and a walled military zone the size of a city itself.

It looks like a scene from a science fiction film. But I saw it firsthand. And it’s very real.

Also Read: Egypt is Building New Delta Artificial River

The Scale of a Nation’s Ambition

The numbers behind the NAC are staggering. Once complete, the project will stretch over 700 square kilometers, making it larger than Singapore. Egypt plans to relocate between 6 and 12 million people here a potential quarter of Cairo’s population.

The city’s skyline is anchored by the Iconic Tower, which reaches 385 meters into the sky, making it the tallest building on the continent. Next to it stands the Grand Mosque of Egypt, capable of hosting over 100,000 worshippers. Sports City offers an Olympic-standard stadium. Nearby, Africa’s largest cathedral, the Nativity of Christ Cathedral, rises as a symbol of religious pluralism.

This isn’t just about architectural grandeur. It’s about a total political and administrative shift. Ministries, the Parliament, the Presidential Palace even foreign embassies are moving to this newly built seat of power.

But behind the steel and concrete lies a question that refuses to go away: why is Egypt building this at all?

Cairo’s Crisis: The Pressure to Escape

Cairo is bursting at the seams. With over 23 million residents, it ranks among the most overcrowded cities on the planet. Decades of neglect have left basic infrastructure failing under its own weight. Millions live in unregulated settlements, often without adequate sanitation or stable electricity. Many buildings teeter in unsafe conditions.

Pollution is crushing. Traffic chokes the streets. Air quality consistently ranks among the worst globally, with vehicles accounting for nearly a third of all emissions. Public transportation is overrun. Hospitals and schools are underfunded. Over 60% of Egyptians live at or below the poverty line.

The government’s answer is to build outward into the desert. Under Egypt Vision 2030, the NAC is marketed as a bold solution: decentralize power, ease Cairo’s population, and start fresh with modern infrastructure.

It sounds logical. But this isn’t the first time Egypt has tried this strategy.

Desert Cities and Broken Promises

Egypt has a long history of building so-called “new cities.” Sadat City, 6th of October City, New Cairo all were planned as escapes from Cairo’s chaos. Most fell short. Many remain half-populated, disconnected from the economic centers, or transformed into gated communities for the elite.

Now, the NAC risks following the same path. Despite its scale, the design raises real concerns. The city’s layout centers on wide highways and massive boulevards, with up to 16-lane roads dividing districts. This makes private vehicles essential, further distancing the city from walkable, human-scale design.

Government and military zones are sealed off behind layers of security. Public accessibility is limited. It’s not just a capital it’s a fortress.

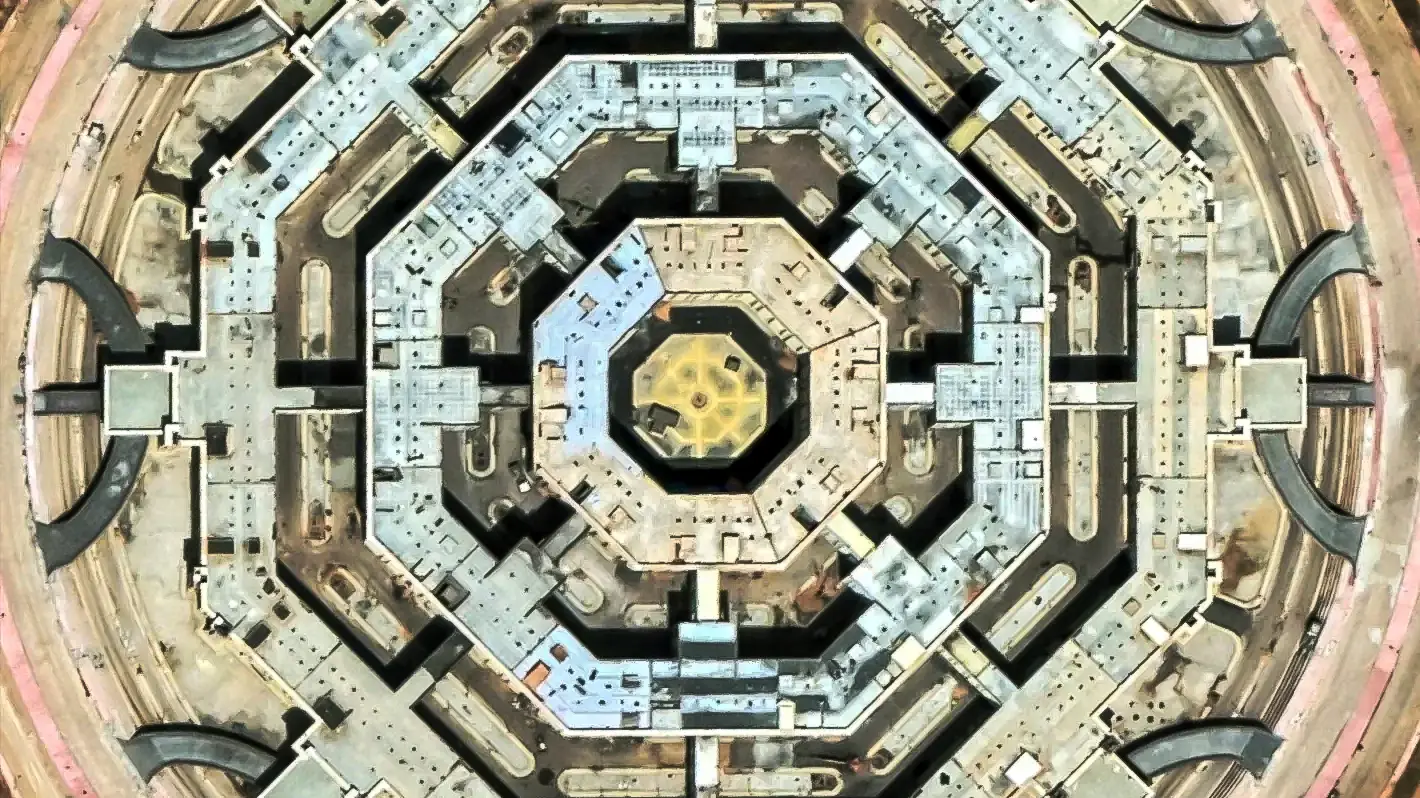

The Octagon and the Military’s Shadow

A critical feature of the NAC is the Octagon, Egypt’s sprawling new military headquarters. Larger than the U.S. Pentagon, the Octagon symbolizes a deepening military presence at the heart of governance.

Roughly 51% of the NAC’s development is controlled by Egypt’s military, through the Armed Forces Engineering Authority and state-owned companies. They control land sales, construction contracts, and large real estate portfolios. There’s no public oversight. Financial details remain classified. In effect, the military owns a city that will generate vast private wealth under the guise of public infrastructure.

For many Egyptians, this raises serious concerns.

A Capital Built to Control, Not Connect

There’s a reason people are comparing the NAC to Naypyidaw, the remote capital built by Myanmar’s military regime. Both cities were built to isolate power from people.

In 2011, Egyptians flooded Cairo’s Tahrir Square, bringing down a 30-year dictatorship. The square’s central location made it a natural rallying point. Protesters could encircle ministries, block access, and disrupt state operations. It was proximity that made the revolution possible.

By shifting power to the NAC behind gates, guarded highways, and military compounds the government removes that proximity. The new capital features over 6,000 surveillance cameras, facial recognition systems, and AI-powered monitoring. Security isn’t a feature here it’s the foundation.

This city isn’t just about modern governance. It’s about ensuring the government can’t be touched.

Also Read: Why Egypt Fears the Construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam?

Who Pays the Price?

The official narrative claims that NAC funding comes from land sales and real estate investments. But much of it is financed through loans from state banks and government borrowing, pushing Egypt further into debt.

The total cost? Over $58 billion more than twice the combined national budgets for health and education.

Meanwhile, everyday Egyptians are struggling. Inflation continues to erode savings. The Egyptian pound has lost significant value. Foreign reserves are shrinking. Imported food, fuel, and medicine have become luxuries. A single apartment in the NAC starts at around $50,000, while the average Egyptian earns barely $3,000 a year.

So the question becomes: who is this city for?

The answer is uncomfortable. It’s for the elite, for government insiders, for military stakeholders, and real estate investors. Not for the millions in Cairo’s decaying districts. Not for the youth struggling to find jobs. And certainly not for the working-class Egyptians who will never afford to live there.

The Numbers Behind the Facade

As of 2024, the NAC has officially entered its second phase. The first phase roughly 168 square kilometers has been developed. Around 100,000 housing units are complete. Government employees are slowly transitioning.

But only about 5,000 families have moved in.

Vacancy rates remain high. Public transportation is limited. Cultural institutions are still under construction. The city lacks the social energy that defines real urban life. What’s built so far feels like a stage waiting for an audience that may never arrive.

Even foreign investors remain cautious. Political instability, economic uncertainty, and lack of transparency have made many wary. What’s billed as Egypt’s future still stands largely empty.

Progress or Monument to Power?

The NAC is a paradox. It reflects a country desperate to modernize, to rise from the ashes of economic struggle, to prove itself on the global stage. A new capital could attract business, offer employment, and redefine African urban planning.

But it also feels like a monument to control. A massive, militarized zone where transparency is optional and privilege is preserved. A place built not to include but to protect those already in power.

Cities are meant to connect people, not shield governments. They’re meant to solve problems, not bury them under glass towers and satellite dishes.

You and I can admire the ambition behind this project. But we can’t ignore what it reveals: a state that is choosing spectacle over substance, separation over solidarity.

Final Thought

The NAC exists. It’s no longer a dream on paper. It’s rising fast, with concrete, glass, and security gates.

But the real question isn’t whether Egypt can build a city in the desert. It’s whether that city will serve the peopl or leave them behind.

I stood at the edge of that new skyline, surrounded by dust and cranes, and I couldn’t shake the feeling: Egypt isn’t just building a capital. It’s building a wall between itself and its own future.