China’s Pinglu Canal: The First New Mega Canal in a Millennium

There is a construction project in southern China that very few outside the country have heard of. It is not a high-speed rail line, a new expressway, or another glass tower rising into the clouds. It is a canal. And not just any canal. Stretching more than 130 kilometers, the Pinglu Canal is the first major canal built anywhere in the world in more than a thousand years.

China is investing over 10 billion dollars into this waterway, cutting through farmland, rock, and urban districts to connect its landlocked interior directly to the South China Sea. When I stood at the excavation site, watching machines carve through the earth, I realized this project could change the movement of goods across Asia as profoundly as the Panama Canal changed the Americas.

China’s Long Canal Legacy

To see why China is returning to canals, you need to look back over a thousand years.

During the Sui and Tang dynasties, Chinese engineers created one of the most ambitious infrastructure projects in history the Grand Canal. Spanning more than 1,700 kilometers, it linked the Yellow River basin with the Yangtze Delta. For centuries, this artery fed cities, supported armies, and carried grain and goods that kept the empire alive.

That golden age of canals faded. Railroads, highways, and aviation took over. Inland shipping shrank, and China poured its resources into high-speed trains and road networks. By the late 20th century, few expected a canal to ever return to center stage.

Now, that has changed. And the reason is both economic and strategic.

Solving China’s Logistics Bottleneck

China’s coastal metropolises Shanghai, Shenzhen, Guangzhou are global giants in shipping and manufacturing. Yet provinces deep inland, like Sichuan, Chongqing, and Guizhou, remain crammed with factories, mines, and steelworks far from seaports. Moving goods from these regions requires a slow journey of over 1,000 kilometers to reach the coast.

Trains and trucks carry much of that load, but costs are high. Road transport consumes fuel and clogs highways, while rail lines are already crowded. For bulk cargo such as coal, ore, or cement, these inefficiencies cut into profits and slow growth.

The Pinglu Canal answers that problem. By connecting Hangzhou’s Xin Reservoir with the Qinjiang River, and eventually the Beibu Gulf, it creates a direct waterborne route to Southeast Asia. This corridor forms a crucial part of China’s Land-Sea Trade Network, a strategy designed to bind inland economies to international markets without relying solely on the congested ports of the east coast.

The economics are undeniable: transporting a ton of goods by water costs about one-fifth of road transport. For industries under pressure from global competition, that cost difference can decide survival.

Engineering on an Unprecedented Scale

Building a canal is not like drawing a blue line across a map. The Pinglu project demands vast engineering feats.

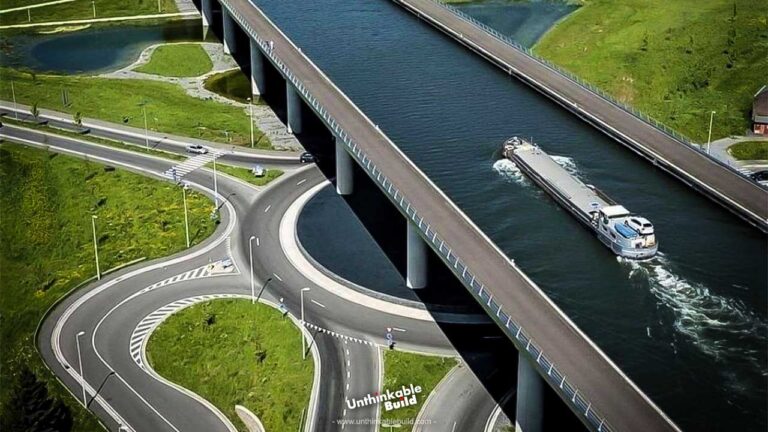

More than 13 million cubic meters of soil and rock are being removed. That’s enough earth to fill 5,000 Olympic swimming pools. The canal requires 90 bridges, long viaducts, and three massive ship locks to manage elevation differences. The centerpiece is the Tiantang Lock, which engineers say will be the largest water-saving lock in the world, capable of raising ships up to 5,000 tons.

The canal also integrates modern logistics technology. Automated traffic control, digital cargo management, and real-time water monitoring will allow ships to move with a precision that older waterways could never achieve. What might have been a 19th-century project has become a 21st-century smart waterway.

Construction began in August 2023, and if deadlines are met, the canal will open by 2026. Once operational, it could handle 95 million tons of cargo each year nearly twice the early traffic of the Panama Canal.

Lessons from Other Global Mega Routes

The Pinglu Canal is not an isolated idea. Around the world, nations are rethinking trade corridors to reshape the flow of goods.

- Arctic Passage: A $43 Billion Sea Route – Melting ice has opened northern waters once blocked for centuries. Russia and China are investing billions into making the Northern Sea Route viable for year-round shipping. This route cuts thousands of kilometers off journeys between Europe and Asia, challenging traditional dominance of the Suez Canal.

- Thailand’s $36 Billion Land Bridge – Instead of digging a canal across the Kra Isthmus, Thailand is planning a massive land bridge to connect the Gulf of Thailand with the Andaman Sea. Twin deep-water ports, linked by rail and highway, aim to rival Singapore and shorten shipping between the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

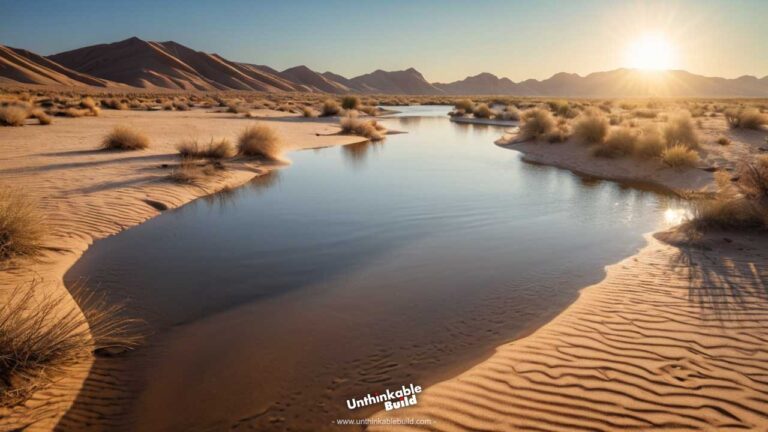

- The Ben Gurion Canal – Israel has revived discussions about a new canal across the Negev Desert, running parallel to the Suez Canal. Though still largely conceptual, it reflects the global race to build redundancy into trade routes.

By comparison, the Pinglu Canal is more focused on internal logistics than global shortcuts, yet its strategic intent feels just as ambitious. Each of these projects signals a shift: nations no longer accept dependence on single chokepoints like Suez or Panama.

Regional and Global Implications

The Pinglu Canal is expected to do far more than save money. Along its length, cities such as Nanning are planning logistics parks, industrial estates, and inland ports. These zones could turn once-isolated provinces into thriving trade hubs.

On a geopolitical level, the canal gives China new options. By linking directly to the Beibu Gulf, China gains quicker and safer access to Southeast Asian markets like Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia. This reduces reliance on routes passing near Taiwan or the heavily contested South China Sea. In an age where trade security carries as much weight as military power, this is a strategic shift.

Social and Environmental Costs

No mega project comes without sacrifice. To make way for the canal, thousands of residents have been relocated. Compensation has been promised, but concerns remain about fairness, cultural displacement, and the loss of ancestral land.

The environmental impact is equally pressing. The canal cuts through wetlands and farmland, while drawing from the Xin Reservoir raises questions about water security. China’s government has pledged mitigation efforts: ecological corridors, silt management, and AI-based water monitoring systems. Yet only years of operation will reveal how well these measures protect the ecosystem.

Climate change adds further uncertainty. Reduced rainfall or extreme flooding could disrupt the canal’s operation. Building resilience into such a massive infrastructure investment will be critical for long-term success.

A Calculated Gamble

The Pinglu Canal is not just a waterway. It is a bet. A bet that inland China can rise as a new driver of global trade. A bet that shipping by canal can still compete in a world of jets, bullet trains, and container megaships. And a bet that development, ecology, and human costs can balance in the face of relentless demand for growth.

If the gamble pays off, the Pinglu Canal could stand alongside the Panama and Suez as one of history’s most important trade arteries. If it fails, it may become another symbol of overreach in the race to build bigger and faster.

When I think about the noise of excavators carving through earth and the sight of villagers watching their old homes vanish into dust, I realize that this canal is more than an engineering project. It is a story about people, power, and the future of trade itself.