The Steel River That Forced Venezuela’s Impossible Oil to Flow

Venezuela holds one of the strangest advantages on Earth. Beneath its soil lies close to 300 billion barrels of proven oil reserves, the largest officially recorded volume in the world according to OPEC and BP Statistical Review data. You might expect this fact alone to guarantee wealth and energy power. The reality feels far more complicated. Most of this oil comes from the Orinoco Belt, and it refuses to behave like ordinary crude. At normal temperatures, it barely moves. It clings. It resists gravity. You can scoop it rather than pour it. Engineers often compare it to asphalt or thick paste. Refineries cannot handle it without modification. Pipelines cannot move it without help. On its own, it brings no economic value at all.

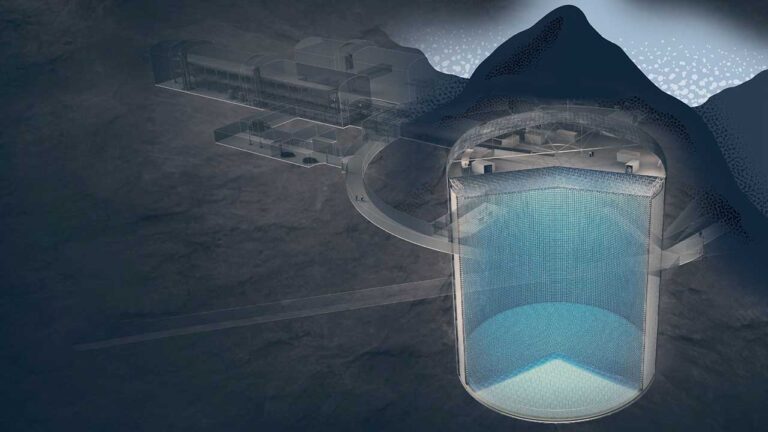

Standing near an Orinoco production site, you feel the contradiction firsthand. I remember watching pumps strain, hearing machinery groan, and realizing that nature had placed a prize underground and locked it behind physics. If Venezuela wanted to turn geology into income, it had to build something extreme. What emerged from that challenge became known in the industry as a steel river.

Also Read: Is Manila’s New Mega-Airport a $15 Billion Mistake?

Oil That Refused to Flow

Heavy crude from the Orinoco Basin contains high sulfur levels, dense hydrocarbons, and abrasive particles. This oil does not simply slide through metal. It scrapes it. It erodes it. It clogs valves and settles in low points. Standard pipelines fail quickly under such conditions.

Transporting millions of barrels per day by truck or rail never made sense. The volumes dwarf any road based system. Only continuous flow infrastructure could work. Pipelines offered the only realistic path to the coast. Yet pipelines designed for light crude would collapse under these conditions.

Engineers faced a simple rule. Either redesign the entire idea of pipeline transport or leave the oil trapped underground.

Designing a Pipeline That Fights Physics

To overcome resistance, engineers increased pipe diameter up to 1.8 meters in some sections. This reduced friction inside the pipe and lowered stress on pumps. They thickened the steel walls to 25 millimeters to withstand abrasion and internal pressure. These pipes needed to last decades under constant strain.

Steel choice mattered. Metallurgists selected alloys that resist corrosion caused by sulfur and acidic compounds. External coatings protect against soil moisture and bacterial corrosion. Internal linings reduce friction and limit metal loss over time.

Every kilometer of pipe became a balance of strength, flexibility, and endurance. The Dilution Solution That Made Movement Possible Even massive steel pipes cannot move paste. Engineers solved this by creating a parallel system. Alongside many heavy oil pipelines runs a second line carrying diluent, a lighter petroleum product such as naphtha or light crude.

At pump stations, operators blend diluent with heavy oil, creating diluted bitumen known as dilbit. This mixture flows at manageable viscosity. Once it reaches coastal terminals, refineries separate the diluent and send it back inland through the return pipeline.

Without this loop, flow stops. This closed system keeps the steel river alive. Canada later adopted similar methods for its oil sands projects, drawing directly from Venezuelan experience.

Manufacturing the Arteries

Pipeline construction begins far from the oil fields. Steel mills roll thick plates, cut them with precision, and bend them into perfect cylinders. Automated welding machines seal each seam. Quality teams inspect every joint using ultrasonic testing and X-ray scans.

Each segment measures roughly 12 to 18 meters long and weighs several tons. Transport crews move these pieces across rough terrain using reinforced trucks and temporary roads. Thousands of segments wait like bones ready to form a skeleton stretching across the country.

Cutting a Route Through a Country

Before installation, construction teams clear a corridor up to 40 meters wide through forests, wetlands, plains, and hills. Environmental teams survey soil stability and water flow. Crews build access roads to support cranes and side booms.

In mountainous zones, controlled explosives carve trenches through rock. In flood plains, drainage systems prevent water accumulation. Workers line trenches with soft sand to protect the pipe from sharp edges and uneven pressure.

This stage reshapes landscapes long before oil ever flows.

Laying the Steel River

Pipe laying demands precision and rhythm. Side boom tractors lift and align segments with careful choreography. Welding teams work in groups that often exceed 70 specialists per spread. A single team completes over 150 welds per day under strict inspection standards.

After welding, technicians scan every joint. Protective polymer coatings seal exposed steel. Only after approval does the pipe descend slowly into the trench. Any misalignment risks long term stress fractures.

This process repeats kilometer after kilometer with no margin for error.

Burial and Long Term Protection

Once placed, workers surround the pipe with fine backfill material. This cushions it from soil movement and seismic vibration. Crews restore original soil layers and compact them with heavy rollers.

Burial protects the pipeline from weather, tampering, and temperature swings. When complete, the land above often returns to farming or natural growth. Few people ever realize a major energy artery runs beneath their feet.

Designed lifespan often exceeds 50 years, assuming constant monitoring and maintenance.

Digital Eyes Underground

Modern heavy oil pipelines rely on advanced monitoring systems. Thousands of sensors track pressure, temperature, and flow rate in real time. Control rooms receive constant data feeds. A sudden pressure drop triggers alerts within seconds. Engineers can shut down pump stations immediately to isolate leaks. This system limits environmental damage and protects infrastructure investment.

Digital oversight transformed pipeline safety standards worldwide. Venezuela adopted many of these systems in later upgrades supported by partnerships with foreign engineering firms before sanctions tightened.

A Backbone of National Survival

These pipelines support nearly all oil exports from eastern Venezuela. Tanker terminals along the Caribbean coast load vessels bound for Asia, Europe, and limited destinations permitted by international policy. Without pipeline flow, exports collapse.

The United States once depended heavily on Venezuelan heavy crude because Gulf Coast refineries were designed to process it. According to U.S. Energy Information Administration data, these refineries handled heavy sour crude more efficiently than lighter shale oil. Structural mismatch reshaped global trade patterns.

Sanctions imposed after 2017 disrupted diluent imports and financing. This caused pipeline utilization rates to drop sharply. China and Russia later stepped in with technical assistance and investment support under revised agreements. Pipelines became instruments of diplomacy as much as engineering.

You can feel this tension when you analyze flow data. Every barrel reflects political alignment and economic survival.

Lessons Exported to the World

Venezuela’s steel river influenced heavy oil projects globally. Engineers applied similar concepts in Canada’s oil sands, Kuwait’s heavy crude expansion, and select Middle Eastern projects. The logic remains universal. Extraction means nothing without transport.

This system proved that resource value begins with movement, not discovery.

The Human Scale of the Project

Thousands of workers built this network under harsh conditions. Welders faced extreme heat. Surveyors crossed swamps and hills. Maintenance crews still inspect remote sections on foot.

I have spoken with engineers who described standing beside a completed line, knowing their work connected buried oil to global markets. That sense of scale changes how you see infrastructure forever.

Also Read: Why Is Singapore Expanding Marina Bay Sands?

A Monument Beneath the Soil

Today, the steel river flows quietly. Pumps hum. Sensors report. Oil moves mile by mile toward the sea. It does not announce itself. It simply works. This pipeline system ranks among the largest and most complex heavy crude transport networks on Earth. It transformed immobile reserves into financial lifelines and reshaped South American energy geography.

Venezuela’s oil still challenges economics, politics, and trust. Yet the engineering solution stands firm. It proves that human ingenuity can force even the most stubborn resource to move. Standing above that buried steel, you realize something powerful. You are not looking at pipes. You are standing on determination turned into infrastructure.