Why Saudi Arabia Shelved the World’s Largest Building Project

Saudi Arabia once set out to construct the largest building humanity had ever imagined. This was not a race for height or skyline symbolism. The goal was mass, volume, and dominance of space on a scale never attempted before. The project promised a single structure measuring 400 meters high, 400 meters wide, and 400 meters long, forming a perfect cube in the center of Riyadh. Engineers planned more than two million square meters of enclosed interior space, sealed, climate-controlled, and unified under one roof. The sheer size alone rivaled entire districts in global cities.

When the Kingdom unveiled the project in 2023, confidence filled every announcement. Official films showed a glowing metallic cube rising from the desert floor. Government officials spoke with certainty. Completion was publicly set for 2030. No contingency language appeared. Saudi Arabia had built a reputation for delivering megaprojects many believed impossible, and I remember watching the reveal thinking the scale felt unreal even by Gulf standards. You could sense the intent to impress the world and reassure the nation at the same time.

Also Read: Saudi Arabia Is Building a Winter City in the Desert Can It Survive?

Then excavation stopped.

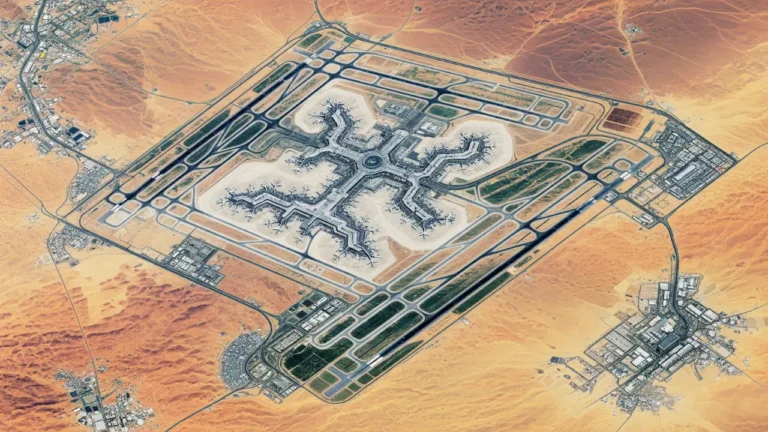

By the time construction slowed, crews had already moved more than ten million cubic meters of earth, according to satellite analysis and reporting from Reuters. The site had become one of the largest excavation zones in Riyadh. Quietly, without announcements or ceremonies, momentum faded. The project remained officially alive, yet progress told a different story. The question began circulating among planners, analysts, and investors alike. Why would Saudi Arabia pause the largest building ever planned after work was already underway.

What the Mukaab Was Designed to Become

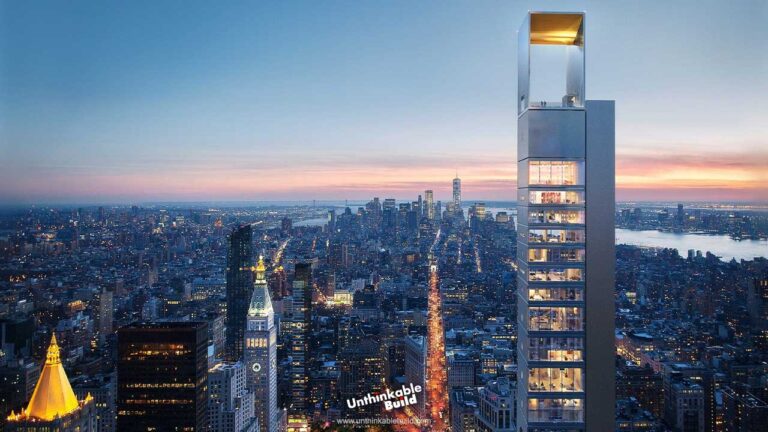

Despite headlines calling it a skyscraper, the Mukaab never fit that definition. The project belonged to the realm of megastructures, closer in spirit to infrastructure than architecture. Its form was a massive cube wrapped in a metallic exterior inspired by traditional Najdi geometric patterns, grounding the structure in local identity rather than global glass-tower aesthetics.

Inside, planners envisioned a fully enclosed interior city. At the center stood a stepped tower, rising more than 300 meters, referencing ancient ziggurats rather than modern spires. Surrounding it, layered platforms would hold apartments, offices, cultural institutions, shopping districts, hotels, and entertainment venues. The entire interior volume would sit beneath an enormous dome integrated with immersive digital systems powered by artificial intelligence. The building itself would function as an environment, not a container.

This was not a place designed for short visits. The concept centered on permanence. Residents could live, work, and socialize without leaving the structure. Designers framed it as a solution to heat, dust, and urban sprawl. It was also a social experiment at a scale no city had tested before. From the start, the Mukaab asked people to accept a fully interior life.

The Economic Weight of a Fifty Billion Dollar Centerpiece

The Mukaab formed the physical and symbolic core of New Murabba, Riyadh’s planned new downtown district. Official estimates placed the cube’s cost near 50 billion US dollars, aligning it with the most expensive infrastructure projects on Earth. The wider development aimed to deliver more than 100,000 residential units and generate hundreds of thousands of jobs. Saudi planners projected an economic contribution of roughly 180 billion Saudi riyals over time.

This development carried major strategic weight under Vision 2030. Riyadh continues to grow fast, with population projections exceeding 15 million residents within the next decade. New Murabba was meant to absorb that growth while positioning the capital as a global business and cultural hub. Early timelines suggested the district would reach maturity before 2030.

As designs matured and cost models tightened, timelines stretched. Completion quietly slipped into the 2040s. That extension changed everything. Long timelines magnify exposure to economic cycles, political risk, and shifts in demand. Each additional year increased uncertainty around financing, leasing, and long-term relevance.

When Construction Momentum Broke

By 2024, excavation neared completion. Foundation works began. Heavy equipment dominated the site. Then progress slowed sharply. Reuters later reported that construction of the cube itself had been suspended beyond early groundwork. Saudi authorities reopened feasibility reviews and financing plans. Infrastructure surrounding New Murabba continued to advance, including roads, utilities, and adjacent developments. The core structure entered limbo.

Officials avoided words like cancellation. The project technically remained part of long-term plans. In practice, the pause sent a powerful signal. In Saudi Arabia, where state-backed megaprojects often proceed without interruption, hesitation carries meaning.

Why the Cube Became Financially Fragile

The Mukaab faced structural challenges beyond engineering. Its greatest weakness lay in how value could be realized. The building could not open in phases. A half-finished cube generates no revenue. Leasing models struggled to define pricing for windowless interior offices spread across massive platforms. Residential demand posed deeper questions. Many people value daylight, outdoor access, and choice. Permanent enclosure appeals to a niche audience, not the mass market required to fill millions of square meters.

No global precedent existed for fully climate-controlled interior volumes of this scale. Insurance pricing remained speculative. Digital infrastructure across such a vast surface added another layer of uncertainty. No confirmed anchor tenants emerged publicly. Vision alone could not secure long-term occupancy.

Even Saudi Arabia, with its scale of capital, could not justify indefinite funding for a structure that depended entirely on full completion before generating returns.

Oil Prices and the Pressure on State Capital

External forces tightened constraints further. In 2025, global oil prices fell close to 60 dollars per barrel. Saudi Arabia’s fiscal breakeven price sat far higher, near 100 dollars per barrel according to International Monetary Fund estimates. Oil still contributes more than 60 percent of government revenue. Price declines translate directly into budget pressure.

The Public Investment Fund oversees assets approaching one trillion dollars, yet much of that wealth remains tied up in long-term holdings with delayed returns. In 2024, disclosures revealed an eight-billion-dollar writedown across several investments. In that climate, projects with uncertain revenue profiles faced tougher scrutiny.

The Mukaab stood exposed. It required sustained funding over decades, lacked phased monetization, and carried demand risk unlike transport infrastructure or housing. Risk managers could not ignore those fundamentals.

A Broader Adjustment Across Vision 2030

The pause reflected a wider shift within Vision 2030. NEOM’s The Line, initially announced as a 170-kilometer linear city, was scaled back and rescheduled deeper into the future. Trojena’s alpine resort ambitions softened. Several high-profile concepts transitioned into more conventional forms.

Saudi Arabia did not abandon transformation. Leadership recalibrated focus toward projects with clearer economic logic, faster delivery, and defined global deadlines. Expo 2030 preparations accelerated. Investment surged ahead of the 2034 FIFA World Cup. Diriyah’s heritage district advanced with strong tourism demand. Qiddiya expanded entertainment infrastructure aligned with domestic consumption.

Capital moved toward logistics hubs, mining, artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and data centers. These sectors offered faster returns and reinforced economic diversification goals without decades-long exposure.

What made the Mukaab different was its location. This pause occurred in Riyadh’s core, not a remote desert frontier. Symbolically, that mattered.

Also Read: UAE’s $13 Billion Mega Rail Will Transform the Middle East

What the Mukaab Ultimately Revealed

The Mukaab did not fail due to ambition. It paused because ambition collided with economic reality at a moment of global tightening. Higher interest rates, cautious capital markets, and shifting urban preferences reshaped the environment faster than concrete could rise.

If excavation alone does not guarantee continuation, a new standard has emerged. Megaprojects now face judgment on flexibility, adaptability, and resilience, not spectacle alone. Scale without optionality carries risk even for states with deep resources.

The world watched Saudi Arabia test the boundaries of human construction. The pause sent a clear signal. The age of unchecked megastructure building has limits. Every vision, no matter how bold, must still answer to time, demand, and economic gravity.

Standing at the edge of what was meant to become the largest building ever conceived, I could sense both ambition and restraint sharing the same ground, and that contrast explains the decision more than any headline ever could.