The Most Extreme Renovation in Canadian History: How Engineers Rebuilt the Heart of a Nation

Canada is carrying out the most extreme renovation project in its history, a construction effort so ambitious that crews spent years carving an enormous underground world beneath Parliament Hill. Engineers began excavation on July 30, 2020, unaware of the scale this operation would reach. By the time the blasting stopped, they had opened a cavern so large it sat in dramatic contrast to the Peace Tower rising above it. All this work focused on one goal: saving a national icon that had quietly moved toward structural and technological failure. I walked the perimeter during one visit, and the sense of scale hit me the moment I saw the bedrock exposed beneath the historic lawn.

Why Ottawa Became the Capital

Ottawa became the capital for reasons that went far beyond symbolism. In the mid-1800s, Queen Victoria needed a site that could bridge the country’s linguistic and cultural divide. Cities like Montreal and Toronto had size and influence, but Ottawa offered position and protection. It sat on the border of Ontario and Quebec, connecting English and French Canada with a sense of balance. Dense forest surrounded the region, adding a layer of security during a period of tension with the United States.

Parliament Hill offered a commanding view above the Ottawa River. It had the space to build a national precinct that could grow with the country. Over time, the Canadian government built a three-block parliamentary complex here, placing the Centre Block at its core. Inside it sat the House of Commons, the Senate, ceremonial rooms, committee spaces, and one of Canada’s greatest architectural treasures: the Library of Parliament. Every major decision in modern Canadian history passed through this building, turning the hill into the platform for national identity.

Also Read: China’s 6th Generation Fighter Jet Shocks the World | The White Emperor Explained

Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of Centre Block

The first Centre Block rose between 1859 and 1876. It reflected the aspirations of a young country, though its life ended abruptly in 1916 when a destructive fire swept through the structure. Only the Library survived, protected by its heavy iron doors and isolated design. A new Centre Block opened in 1927 with a striking Gothic Revival design marked by pointed arches, carved stone, and symbolic ornamentation.

At its heart rose the Peace Tower, built as a memorial to the Canadians who died in the First World War. The tower climbed far higher than the original and carried a 53-bell carillon that could be heard across the city. For generations, this rebuilt Centre Block became the image of Canadian democracy. Its stone exterior appeared timeless from a distance, yet the building was slowly aging from within.

A Building on the Brink

When engineers conducted a full structural assessment, the results showed serious concerns. Concrete supports had eroded. Water had seeped into the walls for decades and corroded the steel inside them. Structural beams showed signs of rust. The building had almost no seismic protection even though the Ottawa region experiences measurable earthquakes. A strong tremor could have caused significant damage.

Material challenges made the situation worse. The Centre Block was constructed using more than 25 types of stone. Each stone aged differently, absorbed moisture differently, and expanded at different rates during freeze–thaw cycles. This made restoration far more complicated than repairing a single material.

At the same time, the building was overwhelmed by millions of visitors each year. It had been designed for a far smaller population and a much lower security footprint. Engineers reached one clear conclusion. Canada had to intervene. With a budget of roughly 5 billion dollars, the country approved the largest restoration project it had ever attempted to protect its parliamentary heart.

The Excavation That Reshaped Parliament Hill

The most striking phase began in 2020. Parliament Hill’s lawn became a 23-metre-deep excavation stretched the entire length of the Centre Block. What had once been a calm public space turned into a massive job site. Crews worked day and night, removing close to 40,000 truckloads of earth and bedrock over three years.

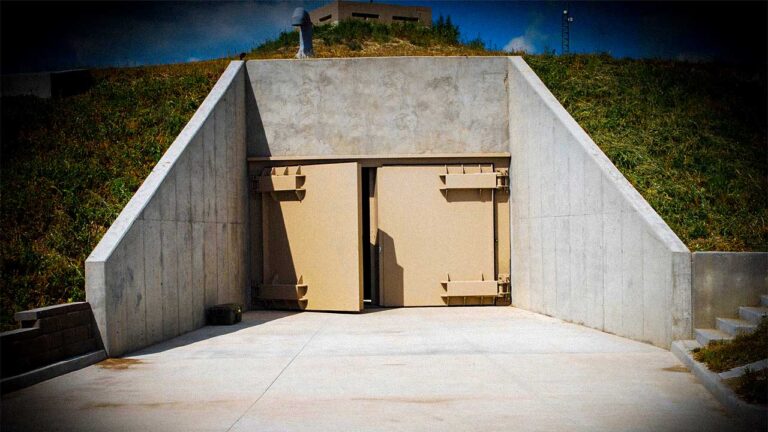

Workers carved directly into ancient rock that had never been exposed before. The goal was bold. Engineers planned to create a multi-level underground Welcome Centre and build a new basement beneath the Centre Block, which had never had proper structural levels below grade. This new space would connect Parliament’s East and West Blocks, shift visitor screening underground, and create a modern entrance that respected the building’s historic character.

The scale made it feel as if a team had decided to strengthen a cathedral by hollowing out the ground beneath it. The work demanded precision because the historic structure above had to remain fully intact.

Engineering a Once-in-a-Generation Solution

After the excavation, the team faced an even harder task. They needed to provide earthquake protection for a century-old building without changing how it looked. Engineers chose base isolation, a method that separates a structure from the ground so it can absorb seismic movement.

Crews installed roughly 800 deep piles beneath and around the original foundation. These piles formed new structural columns that would support the added weight of the modern systems. Workers carefully removed soil between them to create room for more than 500 base isolators. These devices act like massive shock absorbers, allowing the building to move safely during a strong earthquake. The system can shift nearly a metre under heavy motion.

No project in the world had used this specific configuration at this scale. Engineers compared it to performing open-heart surgery on a living building, keeping the historic institution alive while completely rebuilding its core.

Protecting the Peace Tower

The Peace Tower required its own plan. Its carved stone pinnacles are fragile, and even minor vibrations could cause damage. Crews stabilized the tower with reinforced straps and temporary supports. Engineers also rappelled along its walls to inspect the stone around the four clock faces and identify areas that needed reinforcement.

More than 500 sensors were placed across the site to measure vibration, noise, and structural movement in real time. If readings crossed safe limits, work stopped immediately. The tower is more than a structural element; it stands as a national symbol, so its protection carried enormous emotional weight.

Restoring Every Detail Inside and Out

Once the structure was secure, conservation teams shifted to restoration. Workers cleaned and repaired more than 365,000 stones across the exterior. Weather, pollution, and decades of freeze–thaw cycles had caused significant wear. Laser-based techniques allowed crews to remove debris without damaging the stone.

Inside, the work became more intricate. Teams catalogued and preserved more than 20,000 heritage items. They dismantled and rebuilt 50 rooms, repaired wooden carvings, restored historic metalwork, and modernized systems hidden behind walls. Craftspeople also repaired 250 stained-glass windows from the 1920s, bringing new clarity to artwork that had dimmed with age. Every detail mattered because each piece carried meaning from a different moment in Canada’s past.

Parliament in Exile

Democracy had to continue through all of this. The House of Commons moved to the restored West Block, where a glass roof now covers the former courtyard. The Senate relocated to the old central train station, renamed the Senate of Canada Building. These temporary homes will serve Parliament until the Centre Block reopens.

Construction is planned to finish in 2031, with reopening expected the following year. That means an entire generation will grow up with Parliament working outside its historic home, a reminder of how immense this restoration truly is.

Also Read: Thailand’s $36B Land Bridge: Bypassing the World’s Busiest Shipping Lane

A New Welcome Centre Beneath the Hill

The most visible change for visitors will be the new underground Welcome Centre. Instead of climbing the old front steps, guests will follow a raised pathway into a spacious hall built below the surface. The foundations of the Peace Tower will rise inside the atrium as architectural features, showing how the historic and modern structures connect.

Skylights will allow daylight to reach the stone, creating a bright and open environment. The design improves accessibility and security while giving visitors a stronger sense of arrival. It also prepares Parliament for future generations without altering the historic façade.

A Landmark Built to Last Another Century

When the restoration is complete, the Centre Block will look almost unchanged from the outside. Yet beneath that familiar silhouette, it will contain one of the most advanced seismic protection systems in North America, strengthened foundations, modern infrastructure, and thousands of carefully restored details.

Canada is not just repairing a building. It is securing a national symbol so it can stand for the next hundred years. This renovation pushes the boundaries of heritage engineering, showing how a country can preserve its identity while preparing for the future.

This project is more than construction. It is reinvention — a powerful reminder that the structures we inherit deserve the same level of care and respect as the future we build around them.