The Eurasia Canal: The Twenty-Billion-Dollar Waterway That Could Reshape Global Trade

For centuries, canals have changed the course of nations. They cut through deserts, carve new shorelines, and redirect the flow of global commerce. The Suez Canal linked Europe with Asia through a narrow corridor of sand. The Panama Canal opened a new path between the Atlantic and Pacific that reduced journeys from weeks to hours. A new proposal in the heart of Eurasia aims to join that legacy. It’s a 700-kilometer deep-water corridor that would connect the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea and give landlocked Central Asia a long-denied route to open oceans. Backed by Russia and Kazakhstan, and closely watched by China, this twenty-billion-dollar project carries the potential to shift trade patterns across an entire continent. I stood on the shore of the Caspian once, and the sense of isolation from the world’s oceans felt almost physical.

Why This Canal Matters

The Caspian Sea is the world’s largest inland body of water, a basin that holds vast reserves of crude oil, natural gas, grain, and strategic minerals. Countries around its shores rely on these resources to power their economies. Yet the Caspian has one unavoidable limit. It does not connect naturally to any ocean. Every shipment of grain, steel, fuel, or petrochemicals must pass through foreign territory before reaching international waters.

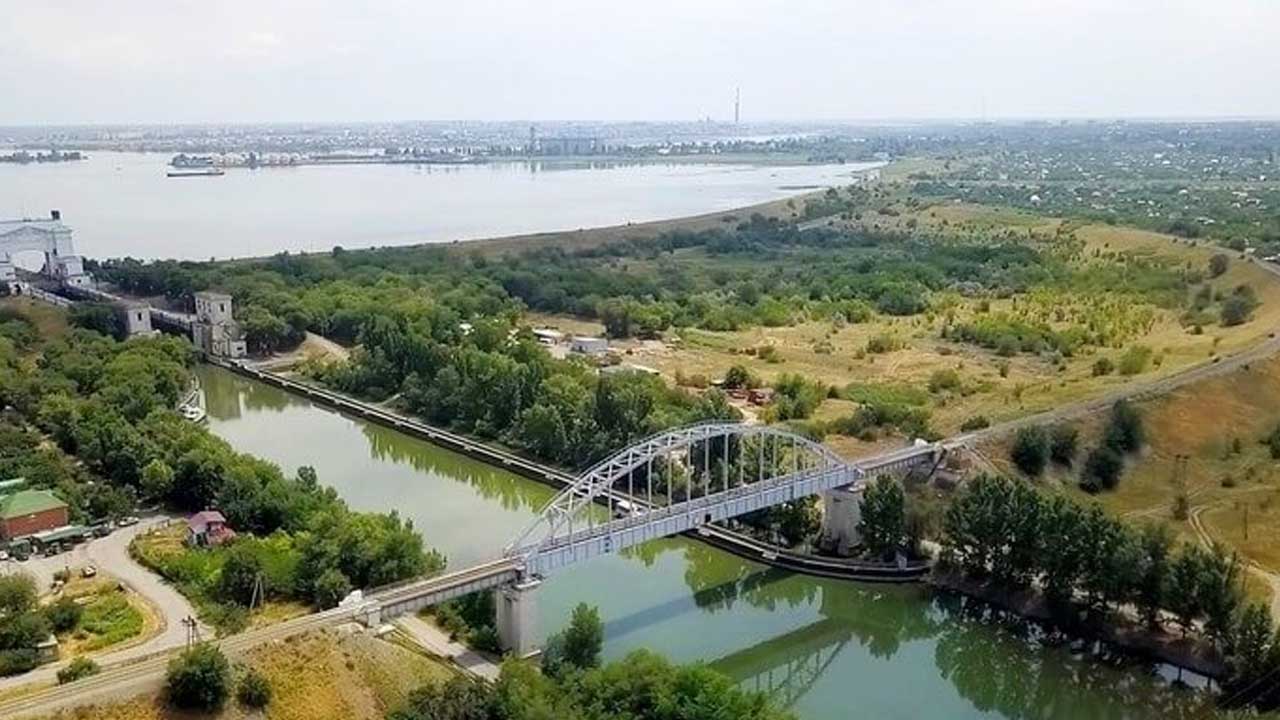

The only maritime route today is the Volga-Don Canal, a system built in 1952 during the Soviet era. Its depth of only 3.5 meters restricts traffic to ships under 5,000 tons. Modern carriers often exceed 20,000 tons, which means they cannot move through the canal at all. The waterway also closes during icy months, and its locks operate under strict schedules. The bottleneck slows exports and raises costs for every country that depends on the Caspian.

Kazakhstan, one of the world’s top ten wheat exporters, faces these challenges every harvest season. It moves grain by rail to ports controlled by other states, paying transit fees that cut into profit margins and reduce global competitiveness. Energy exporters in Turkmenistan and Azerbaijan face similar limits. For decades, the lack of a deep-water outlet shaped the region’s economy, and not in its favor.

Also Read: Saudi–Egypt $4B Red Sea Bridge Connecting Asia & Africa

A Vision That Never Faded

After Kazakhstan gained independence in 1991, the country held abundant natural wealth and a key location but no direct access to the sea. President Nursultan Nazarbayev called this dependence on foreign transit routes a strategic weakness. He believed a deep-water solution could unlock economic growth and national autonomy.

By 2007, Kazakhstan formally approached Russia with a proposal to build a new canal. The idea surfaced at a critical moment. China had begun building massive trade and transport corridors across Central Asia as part of its Belt and Road strategy. A waterway linking the Caspian to the Black Sea aligned with these new routes, offering China another channel to move goods westward.

The concept appealed to all three powers. Russia saw a chance to modernize a key Soviet-era link. Kazakhstan saw a path toward maritime independence. China saw a route that strengthened its foothold across Eurasia. Even after political changes and shifting alliances, the idea survived. It resurfaced in feasibility studies, government meetings, and regional summits. Projects with this level of strategic weight rarely disappear.

Inside the Eurasia Canal Vision

The proposed Eurasia Canal would extend across southern Russia along the Kuma–Manych Depression, a natural valley that stretches between the Caspian Basin and the Black Sea basin. This corridor offers a rare advantage. It avoids mountain ranges, reducing excavation needs and lowering risk across hundreds of kilometers.

Engineers propose a canal depth of roughly 6.5 to 7 meters, enough to support ships between 10,000 and 15,000 tons. That capacity is nearly triple the limit of the Volga-Don route. Projected cargo flow ranges from 75 to 100 million tons per year. If achieved, the canal would rank among the busiest inland waterways on the planet.

Ports around the Caspian, including Kazakhstan’s Aktau and Kuryk, Turkmenistan’s Turkmenbashi, and Russia’s Astrakhan, would gain direct maritime access to the Black Sea. From there, ships could pass through Turkey’s straits to the Mediterranean. For Central Asia, this access would shift the region from landlocked to globally connected.

In 2024, Russia and Kazakhstan renewed discussions through joint working groups, citing the need for a modern transport spine across the region. Updated studies also examined how new cargo demand from China’s westward economic zones could justify the canal’s capacity.

The Engineering Challenge

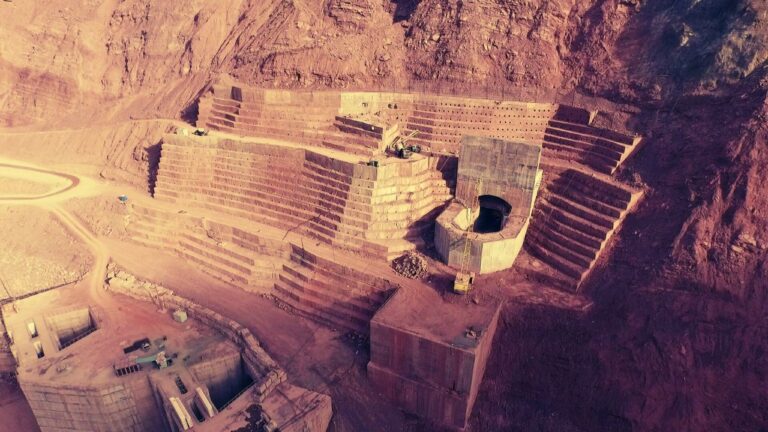

A project of this scale matches the ambition of the world’s largest canals. Engineers would need to excavate hundreds of millions of cubic meters of earth and reshape entire sections of rural southern Russia. The canal would require bridges, service harbors, breakwaters, and support towns along the route.

One of the biggest engineering hurdles comes from elevation. The Caspian Sea sits about 28 meters below global sea level. The Black Sea does not. Water cannot move naturally along this gradient. Engineers would need to construct a series of locks and pumping stations to lift ships up from the Caspian and then lower them again toward the Black Sea. This system resembles the Panama Canal but must be adapted for longer distances and larger vessel classes.

Geology adds another layer of complexity. Much of the Kuma–Manych region is dry steppe with loose soil and zones vulnerable to erosion. Without reinforcement, canal banks could collapse. Engineers would need retaining walls, controlled irrigation systems, and sediment management zones to stabilize the waterway.

Modern navigation technology would guide ships through two-way lanes, using real-time monitoring similar to the systems installed along China’s Grand Canal upgrades. At peak construction, the project could employ tens of thousands of workers across multiple sections, with a build time projected at 10 to 15 years.

The Twenty-Billion-Dollar Question

Cost remains the largest obstacle. Early estimates place the price tag above twenty billion dollars, and updated 2024 assessments suggest the final cost could climb higher due to inflation and material shortages.

Russia supports the plan in principle, but its economy is under pressure and restricted by sanctions. Kazakhstan backs the concept but cannot finance it alone. China remains the strongest potential investor. Chinese banks and engineering firms have experience with megaprojects, including the Kenya Standard Gauge Railway, Pakistan’s Gwadar Port, and massive canal expansions across Southeast Asia. A deep-water corridor through Russia would strengthen China’s westbound freight routes and secure long-term trade access.

Yet investors worry about long payback periods. The canal depends on future cargo volume, political stability, and regional cooperation. Some experts argue that pipelines and railways already dominate Central Asian transport, reducing the need for a waterway. Others say the canal offers resilience and redundancy, especially as climate pressure and geopolitics disrupt existing trade corridors.

Power, Politics, and Regional Tension

A canal of this scale shifts influence across the Caspian region. Iran and Azerbaijan voice concerns that the project would increase Russia’s control over Caspian logistics. Turkmenistan sees opportunity but presses for guarantees on fair access. Turkey, which controls the Bosporus and Dardanelles, remains the final gatekeeper for any ship leaving the Black Sea. No matter how large or efficient the Eurasia Canal becomes, Turkey decides what passes into the Mediterranean.

Trade patterns are changing as well. Global demand for crude oil has slowed growth in some sectors, and many energy shipments now move through pipelines. Critics argue that the canal may not reach its projected cargo volumes. Supporters respond that grain, metals, manufactured goods, and containerized cargo will fill the gap. They view the canal as a long-term asset that strengthens Central Asia’s economic independence.

The Environmental Cost

Environmental impact may prove more decisive than politics or funding. Diverting water and altering natural drainage systems can disrupt entire ecosystems. Wetlands along the Kuma–Manych valley support migratory birds and native fish species. Changes in water flow could damage these habitats.

The Caspian Sea itself faces challenges. Its water level has fallen sharply over the past two decades. Climate models show the decline may continue. Connecting a falling inland sea to an engineered canal requires strict water controls to avoid salinization and soil collapse.

Environmental groups in Russia raised concerns in 2023 and 2024, calling for expanded impact studies and international review. Engineers have proposed fish passages, artificial reservoirs, and controlled flow gates to limit damage. Yet history shows that once a megaproject reshapes a watershed, the effects are often permanent.

Also Read: Inside Bhutan’s $10B Gelephu Mindfulness City: The World’s Most Unusual Urban Experiment

What Comes Next

As of 2025, the Eurasia Canal remains in the feasibility and negotiation phase. Updated technical studies continue, and Russia and Kazakhstan hold regular talks to outline financial models and possible international partnerships. If agreements align, construction could begin late in the decade. A realistic completion window would fall between the late 2030s and early 2040s.

Supporters believe the canal could turn the Caspian region into a major transport hub. Critics argue that the project may never advance beyond planning. Both sides recognize one truth. Megaprojects of this scale depend on timing. The political climate, economic demand, and regional partnerships must converge. Only then can a vision this large move from blueprints to reality.

A Waterway With the Power to Redefine a Continent

If built, the Eurasia Canal could join Suez and Panama as one of the most influential channels in human history. It would open the landlocked center of Eurasia to the ocean for the first time. It would reshape how grain, energy, and raw materials move across continents. It would shift influence, create new trade corridors, and rewrite the strategic map of the region.

For now, the canal remains an idea suspended between ambition and reality. A project bold enough to change the future, waiting for the moment when vision, capital, and politics align.