The Rise and Fall of the Dome at America’s Center: St. Louis’s $720 Million Warning to America

You don’t often hear about a billion-dollar failure hiding in plain sight, but that’s exactly what happened in downtown St. Louis. The Dome at America’s Center, once sold as a symbol of civic rebirth, stands today as a stark reminder of what happens when public dreams collide with private ambition. What started as a desperate attempt to bring back NFL glory turned into one of the most painful betrayals in modern sports history a cautionary tale written in steel, concrete, and broken promises.

I’ve walked through the silent concourses of the Dome, and I’ve felt the weight of what was lost.

A City Desperate for Redemption

When the St. Louis Cardinals football team left for Arizona in 1988, the departure struck deep. The city’s pride took a blow, and fans were left with a painful void. But St. Louis didn’t retreat. Instead, it responded with resolve. Civic leaders crafted a plan to bring football back one that involved building a state-of-the-art domed stadium at public expense.

In 1989, city and state officials approved bonds for the project, with the promise that the new stadium would attract an NFL team. Construction on the $280 million dome began in 1992. The building design included red-tinted concrete, limestone, and brick elements that echoed the city’s historic architecture. This wasn’t just a stadium. It was a mission.

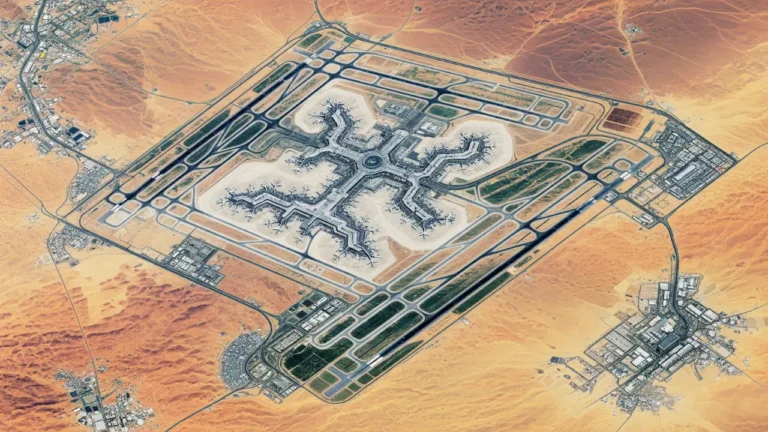

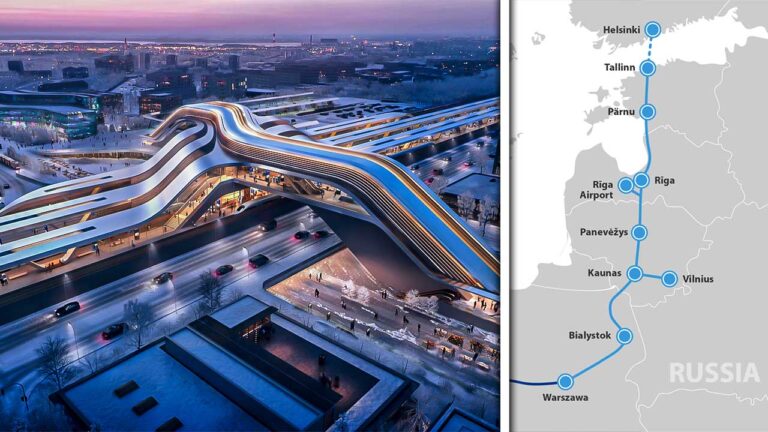

At the time, St. Louis applied for an NFL expansion team but lost out to Jacksonville and Charlotte. The Dome sat empty. But then, a twist of fate changed everything. Before going further did you know How the 2034 FIFA World Cup Will Transform Saudi Arabia?

The Rams Arrive and a New Era Begins

In 1995, Los Angeles Rams owner Georgia Frontiere a St. Louis native pushed for relocation. Initially, NFL owners voted against the move. But legal challenges followed, and eventually the league relented. The Rams moved to St. Louis and played their first games at Busch Memorial Stadium while the Dome finished construction.

On November 12, 1995, the Rams debuted inside their new home, winning 28-17 in front of a packed crowd. The Dome was rebranded as the Trans World Dome, then the Edward Jones Dome. At that moment, it felt like St. Louis had finally won.

And before we go further, consider this: just like St. Louis once pinned its hopes on a stadium, Saudi Arabia is now preparing to reshape its future through the 2034 FIFA World Cup a transformation that could echo the same risks and rewards.

A Stadium Bound by a Fragile Lease

Buried inside the relocation agreement was a condition that would later haunt the city. The Rams’ lease required that the stadium remain in the “top 25 percent” of NFL venues by 2015. If the Dome failed to meet that benchmark, the team could switch to a year-to-year lease or leave without penalty. The clause placed enormous long-term pressure on a city already stretched thin.

In the early years, the stadium seemed adequate. But as NFL teams began building newer, more luxurious stadiums in other cities, the Dome began to fall behind. By the late 2000s, fans were complaining. Sports media called it one of the least appealing venues in professional football.

Poor sightlines. Lackluster atmosphere. Minimal tailgating space. Cold, outdated aesthetics. The signs of decline weren’t just cosmetic they were structural.

A Broken Partnership

In 2009, St. Louis tried to fix the aging Dome. The city poured $30 million into renovations, adding high-definition video boards, improved club areas, and a redesigned locker room. A new AstroTurf system let the field slide into storage. Still, the improvements didn’t meet the lease’s “first-tier” requirement.

In 2012, the city proposed a $48 million upgrade package. The Rams rejected it. Officials came back with a stronger offer $124 million in renovations, with the Rams covering half. Again, the team refused.

Then the Rams unveiled their own vision: a completely new $700 million stadium with a retractable roof and a 360-degree scoreboard. The idea was bold but unrealistic there was no funding, no plan, and no legal obligation for the city to build it. Negotiations collapsed.

By 2013, independent arbitration sided with the Rams. The Dome no longer qualified as a “top-tier” venue. The Rams could walk away at any time.

The Exit Begins in Silence

Behind the scenes, Rams owner Stan Kroenke was already setting his exit plan into motion. In 2014, he bought a 60-acre parcel in Inglewood, California, previously earmarked for a Walmart. It later became the site of SoFi Stadium a $5 billion mega-complex complete with entertainment venues and luxury real estate.

In 2015, Kroenke’s project went public. St. Louis scrambled to keep its team. The city proposed a new stadium on the riverfront, supported by local and state officials. But the NFL wasn’t interested. In January 2016, league owners voted to approve the Rams’ return to Los Angeles.

St. Louis was left behind. The Rams played their final game in the city in December 2015. Edward Jones pulled its sponsorship. The Dome lost its name, its purpose, and its team in one blow.

A Fight for Justice

But St. Louis didn’t go quietly. In 2017, the city, county, and the stadium authority filed a lawsuit against the NFL and the Rams. They accused the league of violating its own relocation rules and misleading local officials during negotiations. The lawsuit uncovered internal NFL documents and emails that confirmed the relocation was planned well before it was announced.

In 2021, the NFL settled. The city was awarded $790 million one of the largest legal settlements in sports history. While the money brought some vindication, it couldn’t bring back the team. It couldn’t reverse the damage to civic pride.

Football Returns in a New Form

Then something unexpected happened. In 2020, the XFL a spring football league announced a new team: the St. Louis Battlehawks. Fans rallied around them with passion that stunned the league. In 2020, over 29,000 fans showed up for their first home game. By 2023, attendance broke 38,000 a record for the league.

The Battlehawks reminded the nation that St. Louis isn’t done with football. The fans still care. The city still believes.

Can the Dome Be Saved?

In 2024, officials proposed a $155 million renovation plan for the Dome at America’s Center. The goal: to upgrade lighting, video boards, sound systems, and bring the venue back into play for major events like NCAA Final Fours and large-scale conventions.

But the question remains who will pay for it?

Ownership of the stadium is split between city and county governments. A portion of the 2021 NFL settlement was set aside for Dome improvements, but it’s not enough to cover the full costs. Public sentiment remains divided. Many see the Dome as a failed investment. Others believe it still holds potential.

There are lessons to be learned from other cities. San Antonio’s Alamodome faced a similar identity crisis. But smart upgrades and a strategy focused on attracting major events brought it back to life. It hosted the NCAA Final Four and drew millions in economic impact. St. Louis could take a similar route but time is running out.

A City at a Crossroads

In 2025, the Dome is scheduled to host more conventions than it has in over a decade. That matters. It shows the structure still has utility, even in a post-NFL world.

After decades of failed bids and near-misses, Morocco is finally stepping onto the world stage. Co-hosting the 2030 FIFA World Cup isn’t the endgame — it’s the beginning of a bold push to claim the final, and reshape global perception through architecture, ambition, and national pride.

This is no longer just a story about football. Yet the deeper question remains: is the Dome worth saving, or should it be replaced entirely?

This is no longer just a story about football. It’s about what happens when cities gamble with public money, chasing dreams sold by billionaires. It’s about accountability, civic pride, and second chances.

St. Louis placed a bet. The Rams walked away with the winnings. And the Dome at America’s Center became a case study in what not to do when negotiating with the NFL.

But maybe just maybe this city still has one more chapter to write.

References: