The 500 Billion Engineering Gamble Behind a Mountain City

Saudi Arabia is attempting something the world has never seen: a mountain city shaped by engineering rather than climate, geology, or natural limits. More than 500 billion dollars anchor this vision inside the NEOM region, where the kingdom plans to carve an alpine destination into the Sarawat Mountains and rewrite how entire cities interact with their environment. This development is known as Trojena, a place designed to deliver snow, lakes, and winter sports in a landscape where summer temperatures across the surrounding deserts often exceed forty degrees Celsius. I remember looking at the early geotechnical reports and realizing how much this project challenges the fundamental rules of mountain construction.

Trojena spans roughly sixty square kilometers of steep slopes, fractured rock, and narrow valleys rising to more than 2600 meters above sea level. Winter temperatures can dip below freezing here, but only for short windows each year. Despite these constraints, Trojena will host the 2029 Asian Winter Games, the first time the event takes place in the Middle East. This aim alone forced engineers, planners, and environmental specialists to confront a question rarely tested at this scale: can you engineer a climate, rebuild water systems from the ground up, and stabilize mountains to behave as the foundations of a functioning city?

Also Read: Atlanta’s $5 Billion Gamble: The Controversial Project Dividing the City

A Mountain System that Resists Easy Construction

The Sarawat Mountains form one of the most rugged geological systems on the Arabian Peninsula. These mountains developed through millions of years of uplift and erosion, leaving behind steep gradients and rock layers that behave differently under stress. Trojena’s subsurface includes brittle igneous formations, metamorphic rocks weakened by shear zones, and faulted layers with unpredictable load paths.

This geology creates challenges rarely seen in traditional urban development. Slopes exceeding thirty degrees apply constant pressure on any structure placed against them. Rainfall, though rare, can fall intensely within short periods, triggering erosion or localized slope failure. Temperature swings of thirty degrees Celsius or more each year introduce expansion and contraction cycles that stress concrete, steel, and anchors. When you build in Riyadh or Dubai, you deal with soil behavior and known bearing conditions. Here, every building must survive shifts in the mountain itself.

Reshaping the Mountains to Make Space for a City

Satellite analyses from 2022 onward confirm that Trojena’s early stages required the removal and redistribution of millions of cubic meters of rock to carve out terraces, platforms, and development zones. These earthworks resemble major global engineering efforts. For reference, Dubai’s Palm Jumeirah needed around ninety-four million cubic meters of sand dredged from the Gulf. Trojena works with hard rock, making excavation slower, more energy-intensive, and more geotechnically sensitive.

Creating room for buildings is only part of the challenge. Trojena requires a network of tunnels beneath the development zone. These tunnels serve water pipelines, electrical systems, slope stabilization anchors, and transit corridors. Tunneling through mixed metamorphic and igneous rock demands precise monitoring because vibrations and voids can destabilize slopes above. Engineers use micro-seismic sensors, 3D ground-penetration mapping, and continuous deformation monitoring to maintain safe excavation boundaries. Minor errors can cascade into large rock movements, so teams measure changes in millimeters.

Engineering a City that Cannot Slide Downhill

Anchoring Trojena’s structures may be one of the most complex geotechnical strategies attempted in a modern city. Engineers drill deep piles into selected bedrock zones to create foundations capable of resisting both gravity and lateral slope movement. Retaining walls hold back regraded mountainsides, with some predicted to exceed fifty meters in height. These walls use post-tensioned concrete, soil nails, and mechanical anchors to counteract both vertical and sideways pressure.

Settlement becomes a long-term concern. Different mountain layers compress at different speeds, which means parts of the same building may shift unevenly. Engineers design structural frames to tolerate this slow movement without cracking or misaligning. Even Trojena’s transportation systems must adapt. Mountain rail lines, cable systems, and roads must flex, drain, and shed weight appropriately or they risk ongoing damage. In a place like Trojena, maintenance is not an occasional task. It becomes the operational backbone of city survival.

Creating Winter in a Region Built by Heat

High altitude alone cannot produce the snow volume required for global ski tourism. Reliable snowmaking becomes essential. To operate efficiently, snow cannons need significant water supply, sustained cold air, and high-pressure pumping systems. Producing artificial snow at scale can require hundreds of thousands of liters per hectare each season. The process consumes large amounts of electricity and demands careful management of temperature and humidity.

The science behind snowmaking at Trojena becomes even more complicated because the natural freezing window is shorter than traditional alpine environments. Engineers rely on advanced wet-bulb temperature monitoring and predictive weather modeling to operate snow systems during optimal hours. The goal is to create slopes suitable for international competitions despite climate conditions that offer limited natural freezing. Snow here is not a gift from the atmosphere. It is an industrial product, engineered and delivered through coordinated systems that must run every winter.

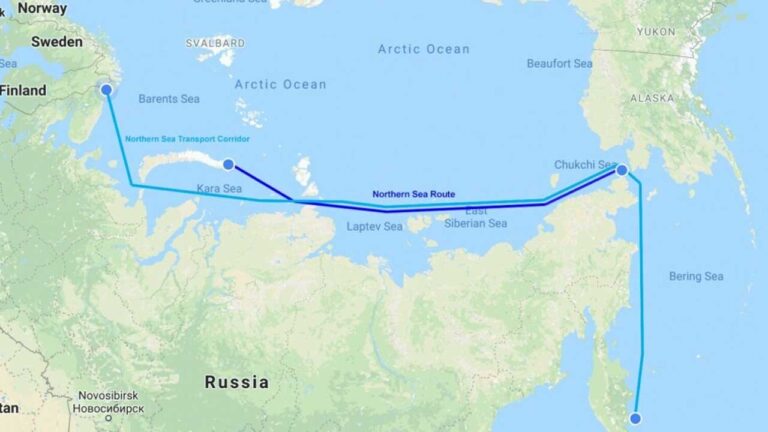

A Water System Lifted Thousands of Meters Against Gravity

All water used at Trojena begins at the Red Sea. Desalination plants along the coast convert seawater into potable water, but the real challenge starts afterward. Trojena sits thousands of meters above the shoreline, requiring high-pressure pump stations to push water uphill through long-distance pipelines. Energy consumption increases with every meter of elevation gained. When combined with artificial lakes, snowmaking, hotels, and residential demand, Trojena becomes one of the most water-intensive developments per capita in the region.

The site’s fractured rock increases water leakage risk. Freeze-thaw cycles can damage pipes and storage systems. Evaporation rises at altitude due to lower atmospheric pressure and stronger sunlight. Retaining water becomes as technically demanding as supplying it.

Delivering Renewable Energy Under Extreme Loads

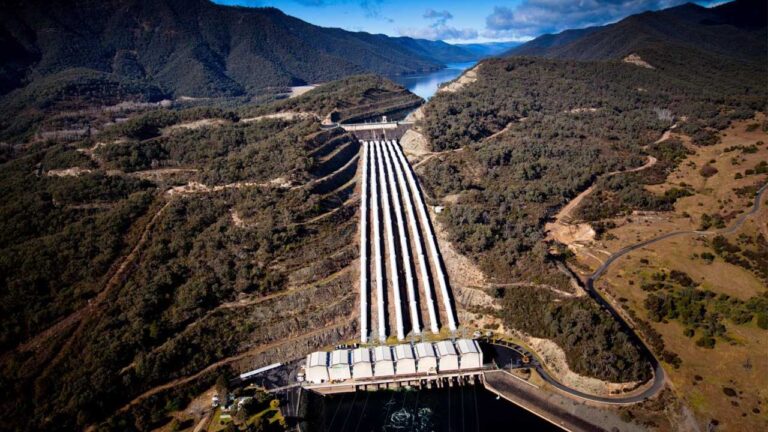

NEOM states that Trojena will operate entirely on renewable energy produced by solar fields, wind farms, and green hydrogen. In principle, these systems can generate significant power. The difficulty lies in meeting peak loads. Snowmaking, desalination, electric transport, and cooling systems often demand maximum power when solar production is low, such as during winter nights.

Continuous energy availability requires large storage systems using batteries, hydrogen buffering, and possibly pumped hydro storage. Engineers must design a hybrid grid capable of sustaining high-altitude operations without interruption. Energy supply becomes a central pillar of Trojena’s viability, not a supporting utility.

Balancing Development and Mountain Ecology

The Sarawat Mountains host species adapted to narrow ecological niches, seasonal migration routes, and soil systems shaped by centuries of rain and erosion. Large-scale grading alters drainage permanently. Artificial snow can increase salinity or alter soil chemistry. Constant water extraction affects aquifers extending far beyond the development zone.

Environmental assessments highlight that many mountain impacts appear only after decades. Vegetation patterns shift slowly. Wildlife adapts gradually or relocates. Engineering can mitigate damage but cannot fully restore original ecological functions once disrupted. Trojena’s planners must balance ambition with long-term stewardship if they want the mountain to remain healthy enough to support the city.

Can Trojena Sustain Itself for Decades?

Trojena aims to attract global tourism, high-income residents, and large sporting events. Luxury real estate, alpine hotels, and digital infrastructure form the economic core. Yet alpine systems are some of the most expensive to maintain. Snowmaking costs increase as global temperatures rise. Stabilization systems require continuous inspection. Water pumping costs escalate with energy prices. Every component of Trojena operates at the limits of climate and engineering.

Viability depends on long-term demand, geopolitical stability, and sustained energy supply. Engineers can design the city. Economists and policymakers must support it through decades of operational complexity.

What Exists Today and What Remains Unproven

Recent satellite imagery shows terraced platforms cut deep into the mountains, expanding access roads, and large-scale excavation zones. These visible changes confirm rapid progress. But the hidden systems—energy storage, long-distance water pumping, artificial climate networks, and snow infrastructure—remain untested at their operational scale.

A city can be built. A stable, functional, resilient mountain city in this environment must prove itself through performance, not blueprints.

Also Read: The Stadium That Cost a City Billions: St. Louis’ Shocking NFL Betrayal

The Mountain as the Final Judge

Trojena pushes engineering into a realm where ambition meets natural resistance. It forces planners to confront whether technology should adapt to harsh environments or reshape them entirely. If Trojena works, it will stand as one of the most impressive demonstrations of coordinated engineering under extreme constraints. If it fails, it may become one of the most expensive lessons in modern construction history.

For now, the outcome remains unwritten. Systems are still rising. Infrastructure continues to evolve. And the mountain, shaped over millions of years, will determine how well a human-made world can hold its ground.