The $400 Million Battle to Control the Pacific’s Deadliest River

At the mouth of the Columbia River, the restless Pacific collides with one of North America’s most powerful waterways. I still remember standing near the shore as towering waves slammed into the river’s current, watching the water fold into itself with violent force. You can feel the danger in the air. This is not Dubai or Bali. This is the infamous Columbia River Bar, a stretch of ocean sailors named the Graveyard of the Pacific after more than two thousand ships met their end here.

For centuries, this narrow passage claimed vessels larger than entire fishing fleets. Swells towered over wooden hulls. Sandbars shifted without warning. Navigation charts failed to keep pace with the constantly changing seabed. Yet today, the same entrance handles billions of dollars in global trade every year. Massive stone jetties stand between safe transit and catastrophe, holding back a meeting of water that never shows mercy. These structures cost nearly $400 million to rebuild and protect, and they remain one of America’s quiet engineering triumphs.

Also Read: Russia’s $300 Billion Arctic Silk Road to Control Global Trade

Why the Columbia River Matters to the Pacific Northwest

The Columbia River begins in the Canadian Rockies and runs 1,243 miles to the Pacific Ocean, draining a basin of more than 258,000 square miles across seven U.S. states and British Columbia. This single waterway sustains farms, factories, ports, tribal fisheries, and power grids across the Pacific Northwest.

Cargo vessels carry almost 50 million tons of freight every year along its channel. Wheat dominates these shipments. Over 40 percent of total U.S. wheat exports leave the country through terminals on the Columbia. Timber, aluminum, wind turbine components, paper products, military equipment, and heavy manufacturing machinery also rely on the river corridor.

Fourteen major hydroelectric dams operate on the Columbia and its tributaries. These dams supply power to millions of homes across Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana. The river also supports salmon runs critical to Indigenous fishing cultures that extend back thousands of years.

This entire industrial network funnels through one narrow exit to the sea. Every vessel depends on safe passage over the Columbia River Bar. If this gateway fails, shipping stalls across half the western United States.

The River Bar That Terrorized Sailors

At the river’s mouth, freshwater collides directly with incoming Pacific swells. The ocean pushes waves inland. The river pushes outward with equal force. This clash stacks water into towering, unpredictable breakers. Hidden beneath the surface, mobile sandbars rise and fall with tide cycles, shifting navigation channels day by day. Some sand ridges reach heights comparable to multi-story buildings under the surface.

Storm systems born in the North Pacific send waves reaching 35 to 40 feet toward the bar. Under these conditions, even modern steel-hulled ships hesitate to cross. For wooden sailing vessels of earlier centuries, the passage bordered on suicidal.

Historical records document more than 2,000 shipwrecks since the 1700s and the loss of over 700 lives. Rescue ships themselves often became casualties. Coast Guard crews regarded bar crossings as among the most dangerous rescue missions anywhere on Earth.

The danger restricted commerce for decades. Ports upriver struggled to grow because vessels hesitated to risk the crossing. Entire regional economies faced limitations imposed by a single natural choke point.

Engineering the Original Jetties

In 1885, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers accepted a challenge few believed possible. Engineers planned to tame the river mouth by forcing water into a single stable navigation channel bounded by large stone jetties. By controlling flow direction, the river’s current would scour sandbars away and allow reliable ship drafts.

Workers began constructing the South Jetty, extending it nearly 6 miles into the Pacific Ocean. Crews dumped millions of tons of basalt rock hauled by railcars from inland quarries directly into pounding surf. Laborers operated off narrow wooden trestles suspended above unstable water, often working just feet from towering waves.

Deaths occurred during construction. Machinery slipped into the ocean. Crews rebuilt washed-out sections again and again.

The North Jetty, completed in 1917, mirrored the southern structure. Together, they forced the river into a narrowed, stabilized channel.

The effect proved dramatic. Sandbars eroded from the channel floor. Ship drafts deepened. Commerce surged upriver almost overnight. Cities like Portland, Vancouver, Longview, and Kalama flourished once safe shipping lanes opened. The Pacific Northwest entered a new industrial chapter fueled by maritime trade.

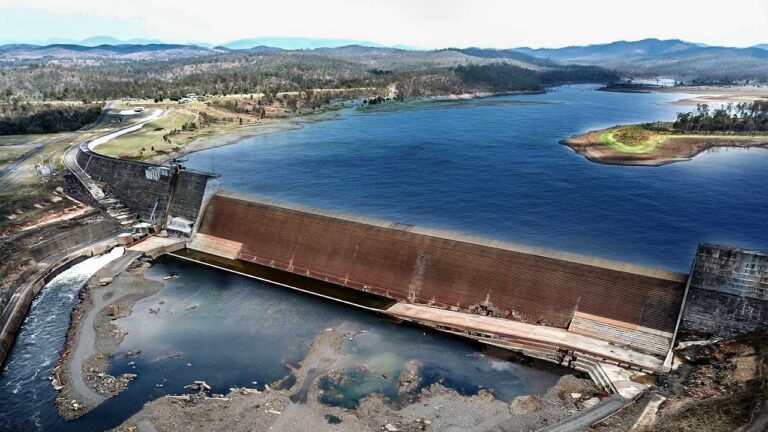

Decay Under Ocean Assault

The ocean never respects permanence. For decades, giant Pacific storms battered the jetties year after year. Waves displaced heavy stone blocks. Water undermined foundations. Erosion progressed unseen beneath the surface until visible collapses began by the 1960s and 1970s.

Segments cracked and slid seaward. Scattered stone weakened flow control. The channel grew unstable again. Mariners reported more hazardous crossings. Federal navigation risk assessments began raising alarms.

By the early 2000s, the Army Corps confirmed that large sections of the jetties had lost structural integrity. Failure threatened to reopen the historic dangers of the Graveyard of the Pacific.

The $400 Million Reconstruction Campaign

In the 2010s, federal agencies launched a multi-phase $400 million rehabilitation program to save the Columbia River entrance. Engineers rebuilt jetties using vastly improved construction methods compared to the 19th century approaches.

The first focus fell on Jetty A, a smaller stabilizing arm protecting the primary navigation corridor. Contractors installed hundreds of thousands of tons of new stone. Completion in 2016 locked the entrance channel into position again.

Next came the North Jetty, rebuilt using GPS-guided heavy-lift cranes mounted on barges that allowed precise placement of stones weighing up to 15 tons each. Engineers fortified foundations and restored original heights to resist wave overtopping.

Crews currently concentrate on reconstructing the South Jetty, the most exposed structure facing the full brute force of Pacific storms. This phase uses stone blocks weighing 18 to 20 tons, each individually positioned to interlock and dissipate wave energy. Barges and cranes operate only during weather windows measured in hours. Saturated seabeds shift constantly beneath foundations, requiring near continuous survey adjustments.

Construction remains limited to the calmer months between May and September. Sudden weather changes still force evacuations, sometimes halting crews for weeks.

A Critical Economic Lifeline

The stabilized entrance now supports the passage of more than 3,600 vessels annually. Total river trade exceeds $24 billion per year. Wheat exports flow efficiently toward Asia. Shipyards maintain steady operations. Fisheries rely on predictable transport channels.

Thousands of maritime jobs across Washington and Oregon depend on the river remaining open. Pilot boats, bar photography teams, tug operators, dredging crews, exporters, customs agents, longshoremen, and emergency responders all rely on jetty reliability.

The Federal Columbia River Bar Pilots Association, one of the most specialized pilot organizations in the world, navigates ships across the entrance daily using advanced radar and tide modeling that supplements jetty protection.

Without these stone barriers, rising insurance premiums and ship safety restrictions alone would devastate regional shipping operations.

The Storms of a Changing Pacific

Climate data shows rising Pacific storm intensities tied to warming ocean patterns. Higher sea levels place greater stress on jetty crests. Long-period wave trains now break deeper into the channel than during the original jetty design era.

The rebuilt structures incorporate new resilience standards. Engineers based spacing and stone sizing models on updated hydrodynamic simulations and severe storm frequency projections extending through the mid-21st century.

This modernization may secure safe passage for the next fifty years, but engineers expect renewed upgrades beyond that horizon. Coastal infrastructure now faces an era of continuous adaptation rather than permanent construction.

Also Read: The $7.5 Billion Airport That’s Making the Rest of the World Look Outdated

A Constant Test of Human Limits

The Columbia River jetties remain one of the clearest demonstrations of humanity’s ongoing struggle against coastal forces. They neither conquer nor submit to the ocean. They hold a negotiated line.

I watched waves slam into newly placed stones and send spray hundreds of feet into the air. You can sense the monumental tension between nature and engineering in every impact. These walls exist only because relentless maintenance continues without pause.

The old sailors were right. The water here never forgives mistakes. Modern commerce survives only because these barriers stand firm.

The battle to control the Pacific’s deadliest river continues stone by stone, dollar by dollar, wave after wave.