Jeddah Tower: The Race to Build the World’s First Kilometer-High Skyscraper

Picture a skyscraper so tall that it dwarfs the Eiffel Tower three times over. A building so high it vanishes into the haze, seemingly piercing the edge of the sky.

This is the Jeddah Tower an ambitious megaproject rising from the sands of Saudi Arabia, designed to reach an unprecedented height of over 1,000 meters. Once complete, it will claim the title of the tallest building in human history.

For years, it has been both a symbol of ambition and a cautionary tale of stalled dreams. But now, after a long halt, cranes are expected to return to the site in 2025, aiming for completion by 2028. I still remember standing at the base of its unfinished core, looking up at concrete that seemed to disappear into the clouds, and feeling the scale hit me in my chest.

The Heart of Jeddah Economic City

Jeddah Tower is not an isolated structure. It is the crown jewel of Jeddah Economic City, a $20 billion urban district under construction just north of Saudi Arabia’s Red Sea port city.

The vision is bold: create an entirely new economic hub from scratch a place where offices, luxury residences, five-star hotels, entertainment complexes, and green public spaces radiate out from a singular landmark. At its full height, Jeddah Tower would surpass the 828-meter Burj Khalifa by more than 170 meters, cementing Saudi Arabia’s place in the elite club of record-setting megaproject nations.

For the Saudi leadership, the tower is a statement a testament to Vision 2030, the kingdom’s long-term plan to diversify away from oil, boost tourism, and showcase its ability to shape the global skyline.

A Timeline of Grand Ambition and Stalled Progress

The idea for the Jeddah Tower emerged in the mid-2000s, during a period when Gulf states were competing to build record-breaking structures. The project was championed by billionaire Prince Al-Waleed bin Talal, whose investment company Kingdom Holding spearheaded development.

By 2013, construction was in full swing. Piling work was complete, the foundation poured, and floor after floor began to rise. By 2017, the structure had reached 63 stories, already a tall building by most standards.

Then came the standstill. In 2018, a sweeping anti-corruption campaign led to arrests of key stakeholders. Payments froze, contractors withdrew, and the site fell silent. The concrete skeleton stood in the desert, baking under the sun.

That changed in late 2023, when the Saudi government reaffirmed the tower’s importance and sought new international contractors. The plan now is to resume construction in 2025 with a renewed timeline targeting 2028 completion.

Engineering at the Edge of Possibility

Building a structure a kilometer high is a unique challenge. The Y-shaped floor plan maximizes stability and reduces wind pressure. Engineers have anchored the tower into Jeddah’s tricky subsoil a mix of limestone and coral using 270 piles, some driven 110 meters deep. Above them lies a 5-meter-thick concrete mat capable of supporting almost a million tons.

Wind tunnel testing has shaped every curve of the design. A central concrete core, paired with tuned mass dampers, helps minimize sway. The lower 600 meters will use high-strength reinforced concrete, while the upper sections will transition to steel to reduce weight.

The Vertical City Experience

Once operational, Jeddah Tower will be like a city in the sky. Three sky lobbies will serve as transfer points between elevator banks, preventing the need for kilometer-long cables. Five double-deck elevators will move at 10 meters per second, among the fastest in the world.

At 600 meters above ground, the observation deck will offer panoramic views that no other building can match surpassing even the heights of Shanghai Tower and Merdeka 118, the newly completed 678.9-meter skyscraper in Kuala Lumpur that currently stands as the world’s second tallest.

Designing for Sustainability

The structure’s tapering profile naturally shades much of its surface, reducing heat gain. Highly reflective glass helps maintain interior temperatures, while chilled air drawn from higher, cooler elevations reduces air conditioning demands. Even the elevators will regenerate electricity during descent, similar to regenerative braking in electric vehicles.

Water condensation from the cooling systems will be recycled for landscaping and maintenance. These measures aim to keep the building’s energy use surprisingly low for its massive scale.

Global Skyscraper Rivalries

The race for height is not unique to Saudi Arabia. Around the world, new towers are vying for superlative status.

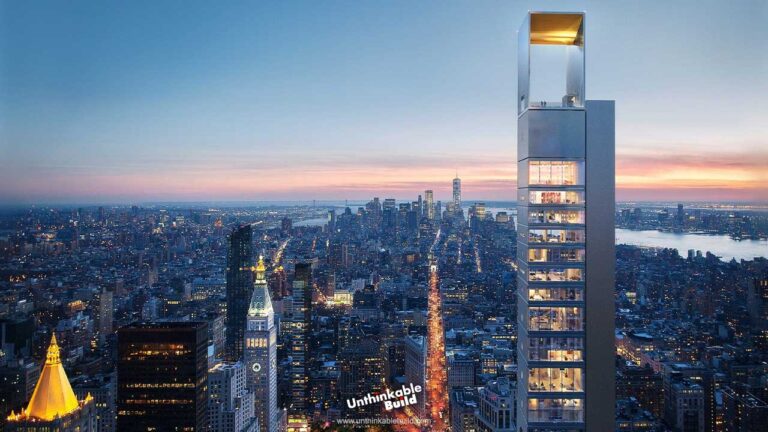

In New York, the planned 262 Fifth Avenue has stirred controversy for its slender profile and impact on Manhattan’s skyline. If completed as proposed, it could become one of the tallest residential buildings in the Western Hemisphere.

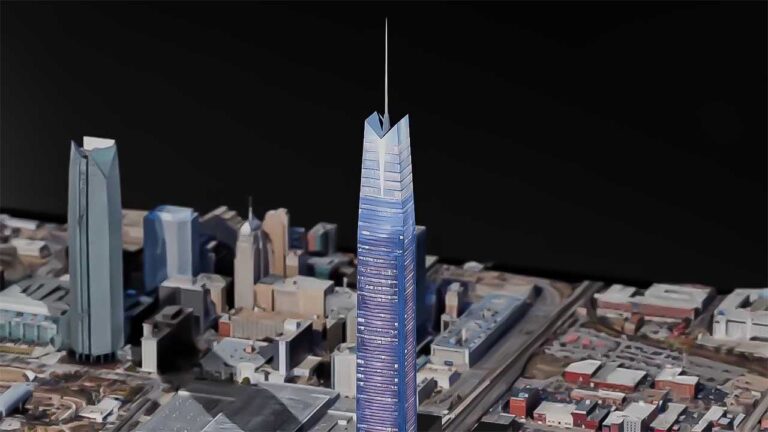

In Oklahoma City, the under-construction Legends Tower could soon claim the title of America’s tallest skyscraper at 581 meters, towering above the current record-holder, One World Trade Center.

In Malaysia, Merdeka 118 recently reached structural completion and is set to open to the public, boasting a height that surpasses every building on Earth except Dubai’s Burj Khalifa and soon, perhaps, Jeddah Tower.

This global competition reflects more than just engineering feats. It’s about prestige, tourism, investment, and the power to define a nation’s image through architecture.

Challenges That Could Shape the Outcome

Even with the revived schedule, Jeddah Tower’s road ahead is filled with challenges. At extreme heights, air density drops, affecting worker safety and construction methods. Pumping concrete hundreds of meters vertically requires specialized equipment and precision timing.

Financing is another question. Building such a structure in an era of fluctuating oil prices and shifting global economies demands unwavering political and financial commitment. The COVID-19 pandemic and inflationary pressures have already reshaped cost estimates.

What Completion Would Mean

If completed as planned, Jeddah Tower would stand as a defining icon of the 21st century. It would demonstrate what human engineering can achieve when ambition and resources align.

For Saudi Arabia, it would mark a strategic pivot from a country known for oil wealth to one capable of delivering landmark projects on a global scale. For architects and engineers, it would set a precedent for the next generation of supertall structures, possibly paving the way for future vertical cities where land scarcity drives urban growth upward.

Standing at the base of its rising core, you can already feel the future taking shape. And whether you see it as a triumph of vision or a risky extravagance, one thing is certain: the world will be watching when the Jeddah Tower finally reaches the clouds.