Hong Kong’s $3.8 Billion Kai Tak Mega Stadium and the High-Stakes Race to Redefine a Global City

On the southern edge of Kowloon’s old runway, I stood where jets once swept low between apartment towers and now watched a 50,000-seat colossus rise beside Victoria Harbour. You can feel the shift immediately. This ground no longer serves departures and arrivals. It now carries the weight of Hong Kong’s ambition. The Kai Tak Sports Park, anchored by Hong Kong’s $3.8 billion mega stadium, represents the largest single sports infrastructure investment in the city’s history and one of the most ambitious stadium projects ever attempted in East Asia.

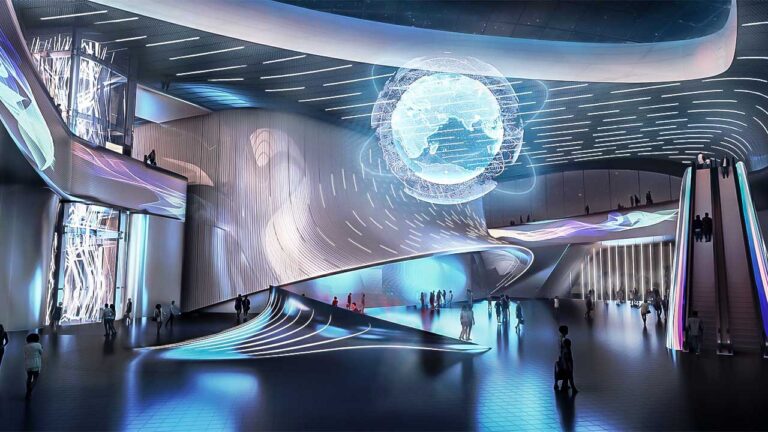

The development aims to reshape Hong Kong’s global identity through sports, concerts, and mass entertainment. I walked the perimeter and imagined the scale of expectation attached to this site. Every beam and panel stands as a statement of intent. This project does not exist for prestige alone. It carries the responsibility of economic return, tourism revival, and international relevance at a time when Hong Kong seeks to reaffirm its place on the world stage.

Why Hong Kong Needed a New Stadium

Sports sit deep within Hong Kong’s cultural fabric. The Hong Kong Rugby Sevens stands among the city’s most recognizable global events. Football matches, cricket tournaments, and basketball games draw loyal followings across age groups. For decades, the Hong Kong Stadium accommodated these events with a capacity near 40,000 seats. Over time, cracks formed both figuratively and literally.

The stadium struggled with persistent noise complaints from surrounding residential towers. Its grass surface failed to meet international standards for multi-sport use. Aging infrastructure limited broadcast capability and hospitality experiences that modern events demand. Public transit bottlenecks irritated spectators. Promoters faced increasing difficulty securing global acts due to restrictive scheduling and technical limitations.

Regional competition intensified pressure. Singapore Sports Hub, opened in 2014, demonstrated how modern multi-use complexes attract constant activity through concerts, tournaments, retail, dining, and daily community programming. Tokyo, Seoul, and Shanghai continued building or upgrading venues with international-grade technology. Hong Kong risked drifting behind economically and culturally without a comparable venue capable of hosting world-class spectacles.

City planners recognized the need for a modern entertainment anchor to retain tourism revenues and secure marquee global events. They also identified sports infrastructure as a driver for youth development, community health initiatives, and creative industry growth. A new stadium required scale, adaptability, and accessibility.

Also Read: Saudi Arabia Is Building a $1 Billion Stadium in the Sky

The Kai Tak Opportunity

Land scarcity defines Hong Kong. Mountains hem in urban sprawl. Harbor waters constrain expansion. Large uninterrupted sites almost never appear inside the city core. The closure of Kai Tak Airport in 1998 changed everything. Its reclaimed runway and surrounding airfield produced 328 hectares of redevelopable land in the heart of Kowloon facing the harbor.

Urban planners envisioned Kai Tak not as a residential zone alone but as a comprehensive mixed-use district. Transportation corridors converged nearby. The MTR Tuen Ma Line, major highways, ferry routes, and expanded pedestrian promenades created exceptional connectivity. This former aviation gateway offered rare spatial freedom for a project no other district could accommodate.

The symbolic transition carried emotional weight. Kai Tak once welcomed the world to Hong Kong from the sky. The Sports Park now seeks to welcome the world on the ground. This transformation aligns with the city’s evolution from manufacturing hub to financial center to tourism and entertainment gateway.

The Sports Park Masterplan

Designers structured the Kai Tak Sports Park as a fully integrated urban campus. The objective extended beyond a single venue. Planners prioritized year-round engagement, mixed programming, and community inclusion.

Main Stadium

At the core stands the 50,000-seat Main Stadium, designed by Populous, the firm behind Wembley Stadium in London and Tottenham Hotspur Stadium. Engineers installed a fully retractable roof that seals the venue for typhoon rains and summer heat. A convertible pitch system switches between hybrid grass and performance flooring for concerts within hours. This flexibility allows continuous booking across sports seasons and touring schedules.

The stadium’s exterior features a sweeping aluminum panel façade inspired by Hong Kong’s nickname, The Pearl of the Orient. Night illumination transforms the shell into a glowing waterfront beacon visible across Victoria Harbour. Sightlines prioritize spectator proximity to the pitch, producing European-style intimacy rather than Olympic-scale distance.

Kai Tak Arena

Adjacent sits the 10,000-seat Kai Tak Arena, optimized for indoor sports and esports tournaments, concerts, exhibitions, gymnastics, and martial arts competitions. Modular seating platforms enable rapid reconfiguration, reducing downtime between events and accommodating broadcast setups for streaming platforms.

Youth Sports Ground

The 5,000-seat Youth Sports Ground anchors the complex’s community mission. Athletics meets, local football tournaments, school competitions, and training programs operate here year-round. This venue embeds the park within daily civic life rather than isolating it as a purely commercial enterprise.

Public Realm and Urban Facilities

The park’s central corridor, Sports Avenue, knits together stadium entries with retail precincts, cafés, food courts, and pedestrian plazas that connect directly to the MTR network. Landscaped waterfront promenades encircle the site with jogging paths, open lawns, outdoor performance spaces, wellness clinics, and cycling networks. A ferry terminal integrates sea transport into the arrival mix.

The design eliminates the barrier mentality typical of stadium districts. Visitors enter through open parks rather than ticket checkpoints. When I walked the avenue, I felt the intention clearly. The park aims to operate like a living neighborhood, not a gated event compound.

Building a $3.8 Billion Mega Structure

Construction began formally in 2019 amid global supply stability. That stability collapsed one year later under the weight of the COVID-19 pandemic. Logistics bottlenecks delayed steel shipments. Labor shortages reduced productivity. Quarantine rules limited on-site staffing. Critical components arrived months late.

The development consortium adjusted architectural specifications to maintain schedule integrity and contain cost escalation. Engineers reduced the number of façade panels from 47,000 to 27,000, preserving geometry while trimming fabrication and installation expense by roughly 25 percent. Structural cores, roof trusses, and seating decks progressed simultaneously to mitigate time losses.

By early 2025, organizers initiated full-capacity stress testing with events that welcomed over 60,000 participants across rehearsals and pilot festivals. Transit platforms, emergency routes, and station crowd flows ran under active monitoring using digital surveillance grids and predictive analytics tools designed to prevent bottlenecks before escalation.

The stadium officially opened in March 2025 with a sold-out Coldplay concert, followed weeks later by the first-ever relocation of the legendary Hong Kong Rugby Sevens to the new venue. Broadcasters reported record ticket sales and improved international viewership metrics tied directly to the stadium’s acoustics and television sightlines.

Financial Pressure and Operational Reality

A stadium’s success depends less on construction spectacle and more on sustained occupancy. The Hong Kong government established performance indicators requiring at least 40 large-scale event days annually and 600,000 paying visitors each year to justify investment stability. Falling short invites long-term public subsidy concerns and underutilization risks.

Event competition remains ruthless. Tokyo Dome City offers year-round programming density. National Stadium Singapore blends government event partnerships with private concert rotations. Seoul’s Olympic facilities draw K-pop tours with homegrown industry backing. Hong Kong must now compete for limited global touring windows and international sports calendars while contending with complex licensing requirements and promoter risk aversion.

Transportation remains the most vulnerable link. Although the MTR provides direct connectivity, surrounding arterial roads still seek completion under overlapping Kai Tak redevelopment schedules. Peak event dispersal pushes network capacity to strain points. Planners experiment with staggered ending times, expanded harbor ferry shuttles, real-time passenger crowd modeling, and geofencing traffic controls.

Operational management contracts emphasize high event turnover rates and hospitality sales growth targets within the attached retail zones. Restaurants and experiential outlets must sustain patronage beyond show nights to maintain district vibrancy.

Strategic and Diplomatic Value

Sports facilities shape geopolitical optics. International hosting projects normalization, accessibility, and hospitality competence. Large visiting audiences create organic cultural exchange beyond formal diplomacy. This stadium allows Hong Kong to re-enter the global events circuit as more than a financial city. It positions the city as an entertainment capital in Asia.

The upcoming 15th National Games of China, scheduled to include major events at Kai Tak, will direct national attention toward Hong Kong with millions of broadcast viewers. Success during this showcase would cement the stadium’s credibility as both a global and domestic flagship venue.

Esports tournaments, international cricket competitions, ice sport showcases, and motorsports exhibitions already appear in preliminary booking discussions based on the stadium’s modular systems and weight-load engineering.

The Long View Forward

Success at Kai Tak depends on constant activation, not landmark novelty. The park must fill weekdays with public programming. It must partner with schools and community clubs. It must cultivate festival calendars that extend tourism seasons beyond traditional peaks. Retail anchors must function independently of event foot traffic.

I watched families use walking tracks long before official opening crowds had arrived. That daily rhythm offers long-term promise. A stadium proves useful when it becomes part of normal life rather than a distant spectacle.

Failure remains a real danger if programming stagnates or financial discipline weakens. Empty seating erodes tourism confidence and burdens taxpayers. Yet the infrastructure itself remains sound. Unlike many white elephant stadiums across Asia, Kai Tak already features a mixed-use ecosystem that reduces reliance on single-sport occupancy.

Also Read: The Stadium That Cost a City Billions: St. Louis’ Shocking NFL Betrayal

A Stadium Built on Risk and Hope

The Kai Tak Mega Stadium stands today as Hong Kong’s boldest public investment in entertainment history. It represents citywide ambition poured into steel, glass, and light. It holds the power to expand tourism revenue, enhance youth sport participation, elevate global perception, and restore international event competitiveness.

Risk shadows its promise. Booking consistency must remain relentless. Transit coordination must improve continuously. Local community integration must deepen to justify its social footprint.

I left the harbour-facing promenade at dusk and watched the façade illuminate across the water, reflecting both courage and pressure. You can almost feel the future inside the structure. Everything depends on what fills the seats and how the city sustains the momentum it has finally achieved.