Belgium’s 7 Billion Dollar Energy Island: Europe’s Green Gamble

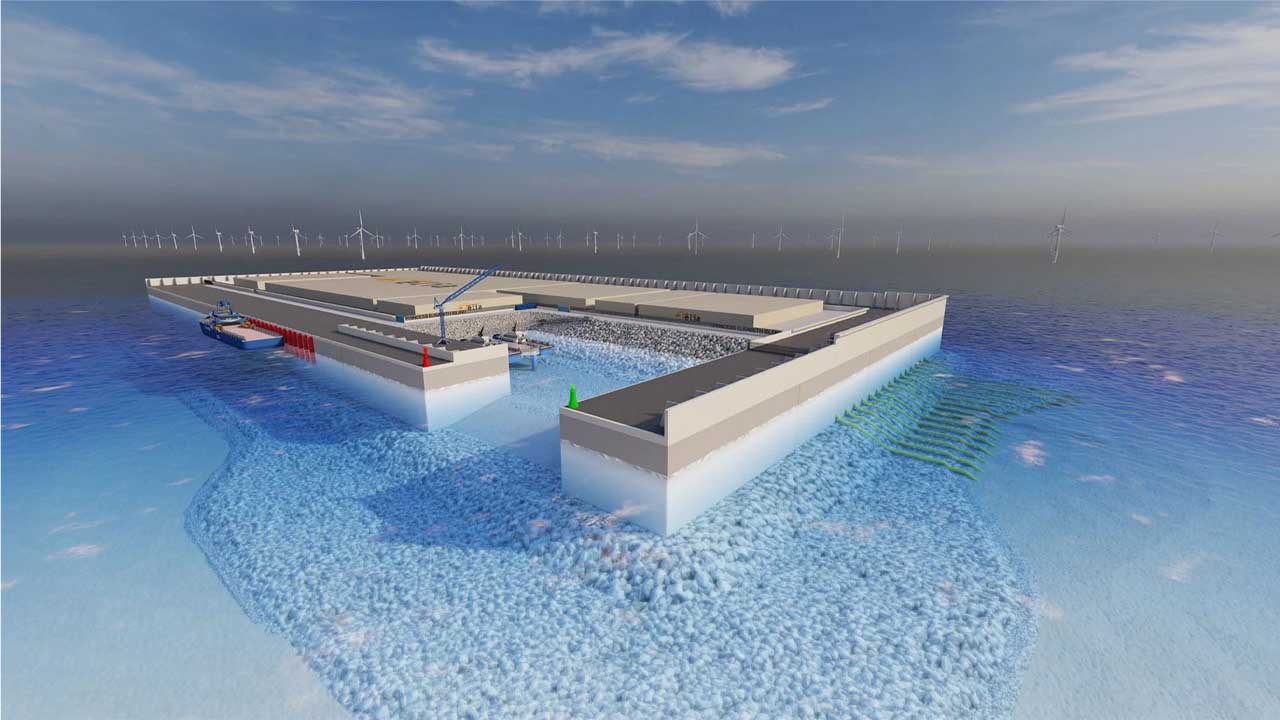

Out in the North Sea, far beyond the Belgian coastline, a project is rising that has no equal in Europe. Belgium is building the first artificial energy island on the planet, a structure engineered to collect, convert, and move clean electricity across the continent. Forty five kilometers from shore, teams are shaping a six hectare platform from steel, concrete, and millions of cubic meters of compacted sand. The goal is simple to describe yet incredibly hard to achieve. Capture the strong offshore winds, process the electricity at sea, then send that power through long undersea cables into Europe’s grid. I felt the scale of this idea the first time I saw detailed construction photos, and it became clear that this is more than a national project. It is a major test of Europe’s clean energy future.

Why Belgium Turned to an Energy Island

Belgium sits among the global leaders in offshore wind production. Eight commercial wind farms already operate in the North Sea, and they supply electricity to millions of homes. Even with this progress, Belgium knows that demand for clean electricity climbs faster than supply can keep up. The national grid cannot handle the next wave of offshore wind without a new system that operates far from the coastline.

Belgium joined eight other North Sea countries in 2016 to explore a coordinated offshore wind hub. The group wanted to share transmission routes, route excess power across borders, and raise production standards across the region. This cooperation gained new urgency when Europe faced the energy shock caused by the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. The crisis exposed how much Europe relied on fuel imports from unstable geopolitical partners. Leaders finally agreed that energy independence required strong renewable systems built inside Europe.

By 2023, the North Sea Summit raised renewable goals to historic levels. Member states committed to quadruple offshore wind capacity by 2030 and reach ten times current production by 2050. Belgium moved quickly. The country identified a strategic zone in the North Sea where large wind farms could link directly into a man-made island built for power conversion. A regional clean energy landmark became essential, not optional.

Also Read: Tuas Mega Port: Inside Singapore’s $20B Plan to Dominate Global Trade

Inside the Princess Elizabeth Energy Island

Princess Elizabeth Energy Island will become the operational center of the Princess Elizabeth Zone, which holds the potential for three new offshore wind farms. Combined, these farms could produce three and a half gigawatts of electricity. That amount can power millions of homes in Belgium and neighboring countries.

The island is not designed as a simple landing point for wind cables. It functions as an electrical crossroads. Engineers will receive alternating current from the wind farms and convert it into high-voltage direct current for long-distance transmission. Direct current reduces energy loss over hundreds of kilometers and keeps electricity stable even in severe weather.

Once the converter stations are installed, the island will host Europe’s next generation of hybrid interconnectors. Nautilus may one day connect Belgium to the United Kingdom. Triton Link is expected to create a route to Denmark. These links will form part of a wider North Sea grid that European planners hope to complete by 2050. If this vision becomes real, the region could produce around 300 gigawatts of clean electricity. That amount equals the combined residential power demand of Germany, France, and the United Kingdom.

Building an Artificial Island from Nothing

Belgium has no natural islands, so engineers are creating one from scratch. The structure relies on enormous concrete caissons that form the external walls. Each caisson measures fifty eight meters in length and weighs twenty two thousand tons. Specialized marine cranes lower these units into position and anchor them eighteen meters deep into the seabed.

The first two caissons were installed in April 2025 during a carefully timed weather window. Construction teams will place twenty three caissons in total. When the ring of walls is complete, the interior will be filled with roughly three million cubic meters of dredged sand. Crews stabilize this material using vibroflotation, a technique that shakes the sand into dense layers until it reaches the hardness of natural rock.

By the time the island reaches its full six hectare footprint, it will host a harbor for small service vessels, a helipad for personnel transfers, and modular housing for teams working offshore. Automation will also play a key role. Offshore robots already tested in Belgian waters will patrol the island and inspect power equipment, cables, and nearby turbines. These machines help crews detect corrosion, structural fatigue, and electrical faults long before they become dangerous.

Engineering Against One of Europe’s Toughest Seas

The North Sea is a demanding place for infrastructure. Waves can climb higher than a four-story building, and winter storms strike with short warning. The seabed shifts in irregular patterns. These risks force engineers to build every component to extreme standards.

The caissons contain ultra high strength steel, and their outer surfaces use abrasion resistant concrete that stands up to constant wave impact. Designers shaped the base to avoid scouring, a process where passing currents erode the seabed below a structure. Every power converter on the island is designed to handle large voltage swings and heavy loads. These converters are the size of buses and weigh hundreds of tons, and only a few manufacturers in the world can produce them. This limited supply has driven up costs across the entire wind industry.

Grid planners created redundant power routes to avoid major outages. If one converter or cable shuts down during a storm, electricity will still move through backup systems. The island’s control center will monitor conditions in real time so that operators can adjust loads and protect the system before incidents spread.

Environmental Stewardship in a Sensitive Marine Zone

Belgium has tried to reduce environmental damage from the start. The project uses low carbon cement, which cuts construction emissions by about forty percent. The shape of the seawall supports marine habitats. Raised ledges offer resting spots for seabirds. Textured concrete sections mimic natural reefs and encourage shellfish and fish populations to return.

Marine teams track changes in water quality, fish behavior, and underwater noise. Early reports indicate that impacts remain limited, though full results will take years to confirm. If researchers find that ecological restoration improves near the island, this project could become a global model for green offshore engineering.

Rising Costs, Delays, and a Tougher Reality

The biggest challenge for the energy island is money. When Belgium first introduced the project in 2021, the cost estimate sat around 2 billion euros. By 2025, this number reached almost 8 billion euros. Costs increased because of rising prices for steel, cement, copper, transformers, and offshore vessels. Countries across the world are competing for the same specialized equipment, and supply chains remain tight.

Independent reviews confirmed that Belgium did not mismanage the project. The price jump reflects global pressures that affect nearly every offshore wind development. In early 2025, national grid operator Elia postponed contracts for the high-voltage direct current systems. Soon after, the government canceled the entire second phase of the island. This decision removed plans for a third wind farm and the future Nautilus cable to the United Kingdom. Belgium now focuses on two wind farms that will produce about 2.1 gigawatts through simpler alternating current transmission.

The timeline has shifted too. Belgium originally aimed for operations to begin around 2030. Recent updates indicate that the island may not become fully active until 2032 or later. Even with this smaller scope, Princess Elizabeth Energy Island remains one of Europe’s most ambitious offshore projects.

Europe’s Broader Challenge

Belgium is not alone. Denmark has pushed its own North Sea energy island plans to 2036. Other countries face similar setbacks. Supply shortages and rising material costs continue to slow progress. Even with these issues, the European Union maintains firm commitments to reach net zero emissions by 2050. Offshore wind must grow to meet that goal.

Hybrid energy islands and international interconnectors remain essential to this strategy. These systems allow countries to share power during shortages, reduce market volatility, and protect households from unpredictable energy prices. Each project brings Europe closer to a more secure and more reliable energy system.

Also Read: The $600 Billion Dam That Could Save Northern Europe

The Meaning of Belgium’s Energy Island

Princess Elizabeth Energy Island represents far more than a construction experiment at sea. It measures Belgium’s ability to build large scale renewable infrastructure under enormous pressure. Success could inspire a new generation of offshore wind systems across Europe, Asia, and North America. Failure would show how fragile the clean energy transition can be when global supply chains become strained.

For now, the world watches as this artificial island slowly rises out of the water. It could become the centerpiece of Europe’s renewable future or one of the most expensive lessons in modern energy planning. I see it as a moment where Europe must prove that ambition and delivery can finally move in the same direction.