The 80 Billion Dollar Dam That Could Power Half of Africa

Deep inside the heart of Central Africa, the Congo River surges through one of the most powerful natural energy corridors on Earth. Standing on its banks near Inga Falls, I felt the raw strength of rushing water vibrating under my feet. That force now drives one of the most ambitious infrastructure plans ever imagined. The Grand Inga Dam carries a price tag of nearly 80 billion dollars and promises to deliver more electricity than any single hydropower project ever built. Engineers designed it to generate more than 40,000 megawatts, an output capable of supplying electricity to almost half of Africa. No dam operating today comes close to its projected scale. Even China’s Three Gorges Dam, the current global heavyweight, produces roughly 22,500 megawatts at full capacity.

The project stands as a response to a crisis that grips an entire continent.

Africa’s energy emergency drives the Grand Inga vision

Africa faces the world’s deepest electricity deficit. The International Energy Agency reports that more than 600 million Africans still live without reliable power access. Updated projections show that population growth could push that number toward 700 million by the early 2030s if power expansion fails to accelerate. Major urban centers such as Lagos, Nairobi, and Kinshasa endure routine outages that cripple hospitals, stall factories, and disrupt daily life. Rural communities often exist in permanent darkness, relying on firewood, diesel generators, or kerosene lamps that damage both health and environment.

Electricity demand across Africa continues rising quickly as cities expand and industries grow. Forecasts from the African Development Bank indicate that continental energy needs may double by 2040. Small solar projects, wind farms, and micro hydro plants play important roles, yet they cannot supply the baseload power required to sustain heavy industry, large hospitals, data centers, and urban rail systems. Many nations still lean on imported diesel fuel or aging coal plants that strain budgets and worsen air pollution.

Also Read: India’s $6.6 Billion Mega Dam That’s Still Not Finished

This gap between demand and supply gave rise to the vision behind Grand Inga. Leaders viewed the Congo River as a natural powerhouse capable of delivering renewable electricity at an unmatched scale.

The Congo River offers unmatched hydropower potential

The Congo River ranks second only to the Amazon in water volume, carrying an average annual discharge near 42,000 cubic meters per second. During rainy seasons, flow surges approach 25,000 cubic meters per second through the steep falls near Inga. This combination of tremendous flow and dramatic elevation drop creates one of the highest hydropower potentials on Earth.

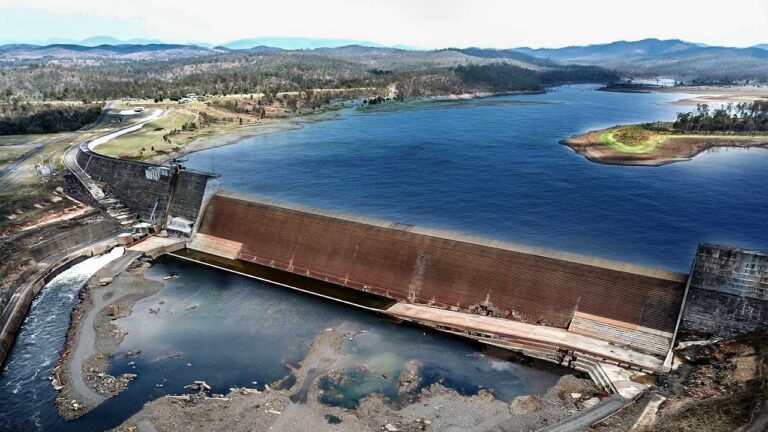

Hydropower studies along the Congo trace back to the 1920s. Colonial engineers recognized the site’s promise but lacked the ability to construct at scale. Development advanced decades later with two smaller dams. Inga 1 entered service in 1972, producing 351 megawatts. Inga 2 followed in 1982 with 1,424 megawatts. Together they harnessed less than five percent of the river’s full potential. Equipment failures, weak maintenance budgets, and political instability eventually reduced operational output far below design levels.

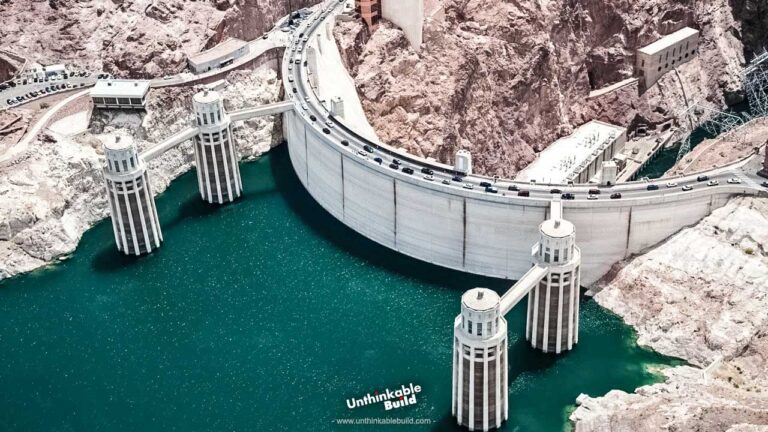

The modern Grand Inga concept expands far beyond those original stations. Phase Inga 3 begins the transformation, targeting roughly 11,000 megawatts once completed. Full build out would add further cascades of dams and channels that push total generation to more than 40,000 megawatts. The complete system plans to use 145 massive turbines positioned along engineered diversion canals rather than a single towering wall. Reservoirs would flood hundreds of square kilometers of lowlands, storing water to maintain power output during seasonal flow changes.

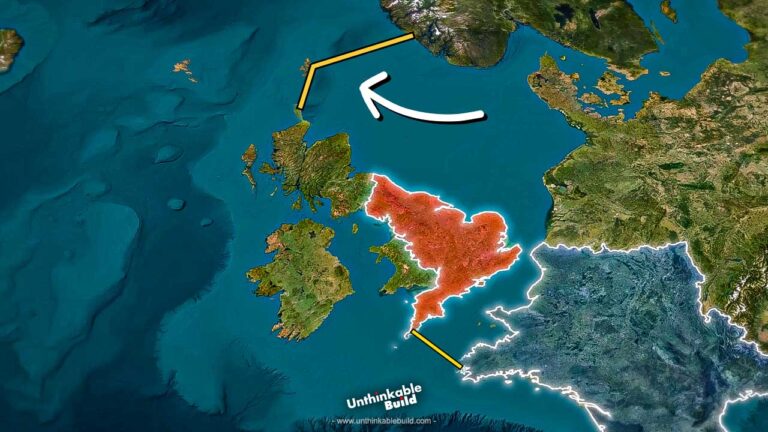

A continental transmission network links nations

Producing electricity at scale represents only half the challenge. Delivering that power across thousands of kilometers presents equal difficulty. The Grand Inga transmission network proposes high voltage direct current lines stretching more than 5,000 kilometers across national borders. Routes would connect the Democratic Republic of Congo to South Africa, Angola, Zambia, Nigeria, and potentially North African grids through transcontinental interconnections.

Engineers selected high voltage direct current technology to limit transmission losses across long distances. Converter stations would step electricity down for local distribution while stabilizing grid performance between countries running different systems. Redundant pathways form part of the design to prevent continental blackouts caused by single line failures.

Recent infrastructure agreements signed with South Africa commit that nation to purchasing several thousand megawatts once Inga 3 reaches completion. Nigeria continues negotiations for westward connections that would feed its rapidly growing industrial economy. These power export contracts form the financial backbone that lenders demand before releasing funding.

Construction faces extraordinary technical challenges

The physical scale of the works pushes engineering into extreme territory. The Congo River’s seasonal surges demand spillways capable of handling water volumes that dwarf most dams worldwide. Engineers designed turbine housings to withstand immense water pressure and heavy sediment loads carried downstream from rainforest tributaries. Sediment abrasion threatens turbine blades and reduces reservoir lifespan unless carefully managed.

Concrete requirements exceed 100 million cubic meters. That volume equals enough material to build several hundred Eiffel Towers. Contractors must excavate thousands of meters of rock for diversion tunnels, turbine halls, and penstock channels. Remote conditions complicate supply chains. Crews navigate dense forests, seasonal floods, tropical humidity, and limited transport routes. Rail spurs and heavy haul roads must reach the site before major equipment arrives.

Advanced sediment flushing systems and fish passage channels aim to reduce ecosystem disruption. Wetland restoration zones form part of long term mitigation plans to counter habitat loss. Reservoir management teams must coordinate water releases to prevent downstream flooding that could threaten communities along riverbanks.

Power grid integration introduces its own risks. Synchronizing electricity flows between unstable national grids demands precise controls and constant uptime monitoring. Engineers design full redundancy systems to isolate network faults quickly and prevent cascading outages across borders.

Economic potential promises sweeping impact

If the project reaches full output, Grand Inga could provide electricity to as many as 600 to 700 million people. Expanded grids could energize schools, clinics, water treatment plants, factories, and agricultural processing hubs. Manufacturing growth alone could lift national incomes by tens of billions of dollars annually, according to assessments by regional development banks.

Construction and operations could employ millions across direct and indirect roles. Skilled laborers support turbine assembly and tunneling operations. Local industries supply cement, transport, and materials. Long term maintenance creates steady employment once the dams operate.

Carbon impact reductions remain substantial. Hydropower generation could prevent millions of tons of carbon dioxide emissions each year by replacing diesel generators and coal stations. This positions the Congo basin as one of the world’s most critical contributors to clean energy transition efforts.

Access to affordable electricity also stabilizes food production through irrigation pumps, refrigeration networks, and fertilizer manufacturing. Rural electrification programs associated with the dam aim to supply power to thousands of villages previously disconnected from national grids.

Human displacement remains a serious cost

Large reservoirs require land, and land supports communities. Preliminary estimates indicate that full Grand Inga development may displace tens of thousands of residents and submerge agricultural land used for subsistence farming. Development agencies require resettlement plans that include housing reconstruction, farmland replacement, job-placement assistance, and access to education services. Past hydro projects across Africa suffered from poor compensation systems that left families worse off.

Current agreements linked to Inga 3 include stronger community protections overseen by international lenders. Independent review bodies conduct impact audits to verify compliance. Civil groups monitor these commitments closely, aware that failures could damage both human lives and project legitimacy.

Also Read: No Workers, Just Robots: Inside the World’s Largest 3D-Printed Dam

Biodiversity disruption also presents risks. The Congo Basin hosts one of the world’s richest ecosystems. Reservoir flooding could eliminate wetland habitats and alter fish migration patterns. Scientists collaborate with engineers to refine seasonal water release schedules that preserve ecological balance to the greatest extent possible.

Political complexity shapes the timetable

Projects of this magnitude demand political unity rarely achieved across developing regions. Grand Inga requires cooperation among multiple African nations, international banks, private investors, and engineering consortiums. Any lapse in governance threatens deadlines and budgets.

Past corruption scandals and management disputes stalled earlier phases and drove away lenders. Recent restructuring placed project oversight under a new authority supported by the African Union and multilateral financing institutions. Transparency agreements now require open procurement processes and third party audits.

Civil unrest in parts of the Democratic Republic of Congo remains a concern. Supply chains depend on stable security corridors for transport and personnel movement. Climate hazards also loom, as extreme flooding events grow more frequent across Central Africa.

Critics argue that decentralized solar and wind installations could deliver faster results at lower initial cost. Supporters respond that scattered renewables cannot sustain heavy industrial growth or regional grids that demand constant baseload supply. For them, Grand Inga stands as the only project capable of meeting Africa’s deep long term energy needs in a single coordinated system.

The future rests on engineering discipline and political will

The current development roadmap targets Inga 3 operational completion around 2035 if financing continues uninterrupted. Full Grand Inga capacity would unfold across two additional decades of staged construction. Each phase finances the next through electricity export revenues.

Standing near the river’s edge, I watched muddy torrents surge past and understood the scale of possibility bound within those waters. Here lies the rare convergence of natural force and human ambition. Grand Inga holds the potential to illuminate dozens of nations, stabilize fragile economies, and position Africa as a global leader in renewable electricity production.

Yet the risk remains sobering. Failure would leave behind abandoned structures, displaced families, damaged ecosystems, and billions lost to unfinished concrete. Success would reshape infrastructure across the continent and prove that coordinated megaproject engineering can lift lives at scale.

Grand Inga is not simply a dam. It stands as a test of governance, collaboration, and technical discipline across borders. It will define an era for African development and perhaps decide how boldly humanity can shape natural power for collective good. I left the river knowing that if this project succeeds, its current will resonate far beyond Congo’s shores, lighting homes and fueling dreams across an entire continent.