The World’s First Floating City Is Being Built Right Now

Along a calm stretch of South Korea’s southern coastline, engineers, architects, and marine specialists are attempting something humanity has never completed at city scale before. They are building a community designed to float permanently on the open sea. When I first studied the scale of this effort, I realized this was not an architectural stunt or a luxury experiment. It is a response to a crisis already in motion, one that you and I cannot avoid. The project is called Oceanix Busan, and it stands as the world’s first government backed floating city prototype.

Rising oceans now threaten the lives and homes of hundreds of millions of people. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projects global sea levels will rise up to 1.1 meters by 2100 under current emissions trends. That figure hides its true impact. Even a half meter increase displaces entire urban districts, contaminates freshwater systems, increases storm surge damage, and erodes coastlines beyond repair. When I visit coastal cities today, I see flood barriers stacked like panic defenses. Yet water still pours in during storms, and insurance companies already withdraw coverage from the most vulnerable zones.

Bangladesh houses over 30 million people less than a meter above sea level. Annual floods erase homes faster than communities can rebuild. Jakarta sinks by 7 to 10 centimeters every year, driven by groundwater extraction combined with rising seas. Indonesia plans to relocate its capital because one third of Jakarta could sit underwater by mid century. The Maldives’ highest natural point reaches only 2.4 meters above sea level. Scientists warn entire atolls may disappear well before 2100. Miami now experiences chronic tidal flooding even on sunny days. New York, London, and Shanghai spend billions reinforcing coastlines, yet hurricanes and storm surges keep overwhelming those defenses.

Also Read: The World’s Tallest Abandoned Skyscraper Is Rising Again (597m)

The World Bank estimates global coastal flooding losses could exceed $14 trillion annually by 2050. Seawalls and levees fail under mounting pressure. Pump systems demand continuous electricity. Land reclamation grows increasingly expensive. Engineers now face a hard truth. Fighting water alone replaces prevention with endless repair. Some designers now ask a different question. What if cities could live with the ocean instead of resisting it.

Oceanix Busan and the Birth of Floating Urbanism

In 2019, the United Nations Human Settlements Programme partnered with Bjarke Ingels Group, MIT’s Center for Ocean Engineering, and the firm Oceanix to develop a practical model for floating urban settlements. They focused on affordability, durability, emissions reduction, and the ability to scale. These teams selected Busan, South Korea’s major port city, as the world’s first pilot location. The South Korean government formally endorsed the initiative in 2022, moving Oceanix from concept art into physical development.

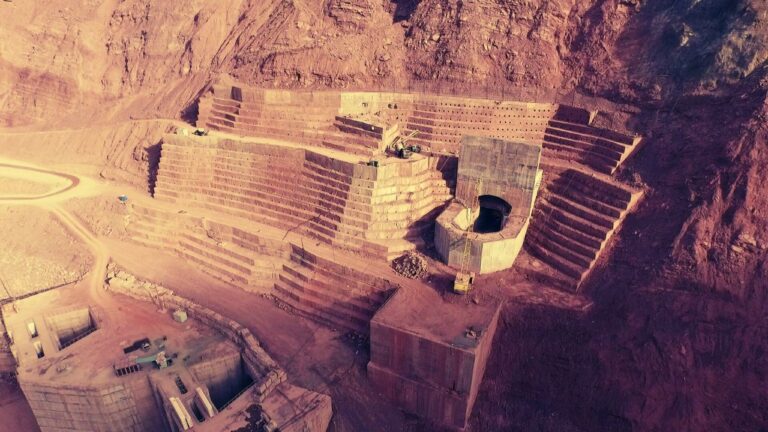

The pilot site spans 6.3 hectares, roughly the area of eight football fields. The design starts with three hexagonal platforms anchored close to Busan’s shoreline. Future expansion could add up to twenty platforms capable of supporting approximately 12,000 residents. Each platform hosts housing units, community facilities, research laboratories, schools, and small commercial spaces. Designers selected hexagonal structures for stability and modular expansion. The shape distributes wave energy evenly while allowing seamless connection between modules. The platforms function like urban puzzle pieces that grow into districts as population increases.

From above, Oceanix Busan resembles an artificial archipelago encircled by water. Solar covered rooftops sit alongside terraced gardens. Pedestrian walkways connect residential clusters to floating plazas and sheltered harbors. Rather than copying dense inland building styles, architects kept structures low rise to minimize wind exposure and reduce material demands.

Oceanix never marketed the city as a luxury resort or elite retreat. Every document frames it as a prototype refugee city model, a system that vulnerable nations could replicate to preserve population centers lost to climate displacement. That goal reshaped every structural decision.

Engineering the Future City at Sea

Designing a floating city introduces challenges that push maritime engineering into new territory. Each Oceanix platform uses a tension leg anchoring system secured deep into the seabed. These anchors allow controlled vertical movement with tides while preventing lateral drift during storms. The platforms remain stable during wave conditions equivalent to Category 5 hurricanes, with wave resistance designed for heights exceeding seven meters.

Power systems rely entirely on renewables. Solar panels dominate rooftop surfaces, supplying most daily electrical demand. Supplemental power comes from offshore wind turbines and experimental ocean thermal energy conversion systems, which draw temperature differentials from seawater layers to generate electricity. The goal eliminates fossil fuel use entirely.

Water infrastructure operates independently. Desalination plants convert seawater into potable water. Rainwater harvesting systems capture seasonal precipitation. On site greywater recycling plants reroute used household water for agricultural and sanitation purposes. City planners aim to maintain permanent water security regardless of rainfall variability or mainland disruptions.

Food production remains local and marine based. Engineers deploy aquaponic farms, merging fish cultivation with hydroponic vegetable systems. Fish waste nourishes plants while plants naturally filter water in closed loop circulation. Rooftop gardens grow supplemental produce. Scaling projections suggest mature platform clusters could achieve near full food independence.

Waste management eliminates ocean discharge. Organic waste converts into compost or biogas energy. Recyclable materials reenter manufacturing loops hosted directly on the platforms. No untreated refuse leaves the settlement or contaminates surrounding waters.

Building materials emphasize carbon reduction and structural resilience. Residential buildings rely heavily on cross laminated timber, known for earthquake flexibility and low embodied carbon. Bamboo composites provide cladding reinforcement. Platform substrates employ Biorock structures, a marine grown limestone material formed by electro mineral accretion. Research demonstrates Biorock gains strength over time and self heals minor cracks when exposed to seawater minerals. Its strength surpasses standard concrete while regenerating surface layers naturally.

The pilot construction budget stands at approximately $200 million, covering platform fabrication, utility systems, renewable installations, and public facilities. Critics highlight its cost per resident. Development teams counter that scaling reduces expenses dramatically, allowing platform production costs to drop once manufacturing moves into mass volume.

Global Demand for Floating Cities

Some nations already experiment independently with ocean living. The Maldives works with Dutch marine engineers to develop floating neighborhoods near Male, targeting housing for 5,000 residents in its first deployment. Flood prone communities in Bangladesh operate floating schools, clinics, and farms to sustain education and income during monsoon seasons. Pacific island nations like Kiribati and Tuvalu lobby the United Nations for legal recognition of displaced maritime populations as rising seas threaten territorial extinction.

The Netherlands maintains several floating housing districts near Amsterdam that operate successfully under strict storm resilience codes. Japan invests heavily in offshore wind platform technology that may one day support full maritime residential zones tied to energy production infrastructure.

Yet Oceanix Busan represents the first integrated floating urban ecosystem backed directly by both national government authority and UN oversight. Its progress determines whether floating megacities remain visionary sketches or evolve into a global survival method.

Legal, Environmental, and Political Questions

Critics raise realistic concerns. Cost control remains unresolved for developing nations that face the most urgent displacement. Financing structures depend on international climate funds that fluctuate with politics. Environmental researchers monitor anchoring operations to prevent coral damage and seabed disruption. Marine biodiversity remains a critical design variable as large floating installations alter light penetration and local ecosystems.

Jurisdiction questions continue unresolved. Floating cities near national coastlines fall under domestic law. Cities expanding into international waters enter legal ambiguity. Maritime law offers no standardized governance frameworks for permanent urban citizens living offshore. Questions arise over taxation authority, citizenship rights, emergency jurisdiction, and law enforcement access.

Social inequality risks persist. Some analysts fear floating cities may become safe havens for wealthy populations escaping coastal decay rather than housing displaced citizens. Oceanix leadership counters this narrative with design affordability benchmarks and local employment integration models, but no true real world data exists yet because full occupancy has not begun.

Also read: The World’s First AI Fighter Jet

What Oceanix Busan Represents?

Oceanix Busan shows humanity’s first serious attempt to construct a permanent urban environment that treats water not as an enemy but as its foundation. Its success or failure influences far more than a single coastal city. If the pilot reaches stable long term habitation, governments may rewrite urban planning rules for threatened megacities from Mumbai to Lagos. Climate migration policies could pivot toward marine relocation options rather than mass inland displacement.

For the first time, cities could expand seaward without destroying fragile wetlands or erecting endless wall systems. Floating districts could relieve housing shortages while preserving ecosystems instead of burying them beneath reclaimed land.

If Oceanix Busan fails, cities may remain chained to land based defenses against an ocean that never stops rising. Seawalls may grow taller. Cost may rise higher. Evacuations may become more common. Millions could lose ancestral homes without replacement strategies.

I studied engineering megaprojects for years, but few initiatives feel as consequential as this. For the first time, human settlements challenge the boundaries between land and sea with practical intent rather than fantasy. Oceanix Busan stands not as a showpiece of architectural ambition but as a real world prototype for survival driven by necessity.

A city now floats where concrete once ruled. The question no longer asks if humans can build on water. It asks if we can adapt fast enough to live there before rising seas take what remains of the shorelines we depended on for centuries.