Saudi–Egypt Red Sea Bridge: The 32-Kilometer Mega Project Connecting Asia and Africa

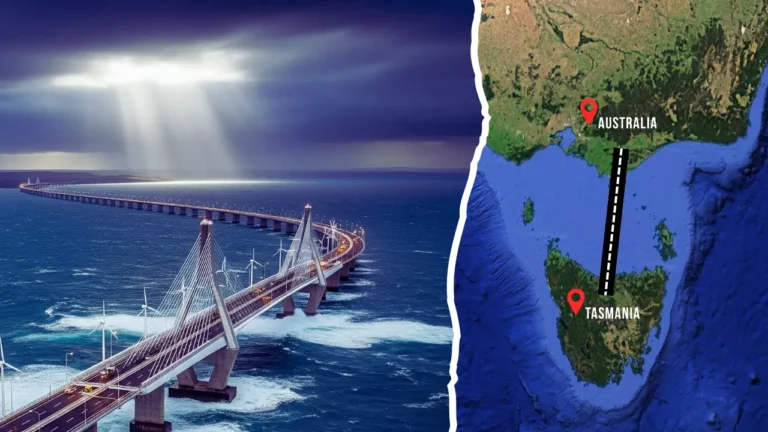

The Red Sea has always been a natural divide between Asia and Africa, but Saudi Arabia and Egypt are working on a plan that could change that forever. Their vision is bold a massive bridge spanning nearly 32 kilometers, physically linking the Arabian Peninsula to the African continent. It’s a connection that could redraw global trade routes, unlock billions in tourism, and tie two of the world’s most strategically important nations together in a way that has never been done before.

This isn’t a single roadway suspended over water. It’s a complex network of causeways, towering suspension sections, and possibly even underwater tunnels. Cars, freight trains, and high-speed passenger rail would all share the same corridor, allowing someone to travel from the Persian Gulf to Cairo without boarding a ship or plane.

Saudi–Egypt Red Sea Bridge

The proposed Saudi–Egypt Red Sea Bridge would cross the Strait of Tiran, the narrow yet deep channel between Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula and Saudi Arabia’s Tabuk region. Its planned length of 32 kilometers (about 20 miles) would surpass many iconic spans, placing it among the world’s largest overwater connections.

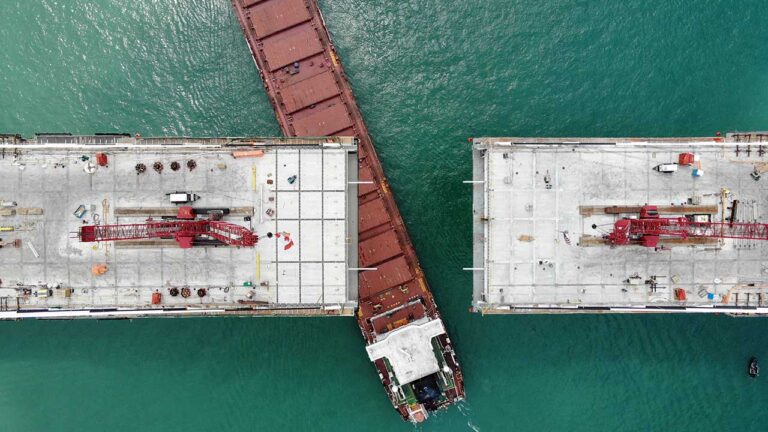

Design studies suggest it could combine long causeways over shallow reef zones with massive suspension spans to cross deep water, and possibly tunnel sections to avoid disturbing fragile marine habitats and busy shipping routes. These multi-modal lanes wouldn’t just serve vehicles the integration of rail could plug directly into Saudi Arabia’s developing Landbridge rail project and Egypt’s national railway system, creating a continuous land link between the Middle East and North Africa.

In terms of cost, early estimates hover around $4 billion, but with environmental protection measures and seismic reinforcement, the final figure could be significantly higher. Planners are targeting an eight-year build time once work begins, but with a project of this complexity, even a small delay can shift the timeline by years.

Four Decades in the Making

The idea of a bridge here isn’t new. Initial proposals date back to the early 1980s, but political tensions, economic limitations, and technical uncertainties kept it from advancing.

Momentum picked up in 2016 when King Salman of Saudi Arabia and Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi signed agreements that included Egypt’s recognition of Saudi sovereignty over the Tiran and Sanafir Islands the likely anchor points for the bridge’s supports. That political clearance was a major hurdle.

Now in 2025, feasibility studies are nearly complete. Environmental impact assessments are in their final phase. Engineers are testing models to address seismic risk and protect coral ecosystems, with the possibility of replacing certain sections with deep-bore tunnels.

Economic and Strategic Stakes

The economic case is clear: the bridge could cut transit times for goods moving between Asia and Africa, bypassing the need to route shipments through longer maritime paths around the Arabian Peninsula or congested hubs like the Suez Canal. This direct overland route could lower freight costs and increase regional competitiveness.

Tourism is a huge driver too. Egyptian officials project that the Sinai region could see tourist arrivals quadruple from about 300,000 annually to well over a million. Saudi Arabia wants it integrated into its Vision 2030 mega projects, alongside NEOM and the Red Sea Project, which together are transforming its northwest coast into a luxury tourism corridor.

Symbolically, this crossing sits near one of the most storied locations in religious history the area traditionally associated with Moses parting the Red Sea. Some see the bridge as an engineering parallel to that legendary crossing.

Engineering and Environmental Realities

Beneath its surface beauty, the Strait of Tiran presents formidable engineering challenges. Its depth reaches nearly 290 meters, which complicates pylon construction. The area is also seismically active, requiring the bridge to be earthquake-resistant, similar to the engineering strategies used for Japan’s Akashi Kaikyo Bridge the world’s longest central span suspension bridge at 1,991 meters and the Gordie Howe International Bridge in North America, which at 853 meters will be the longest cable-stayed bridge on the continent when completed in 2025.

Environmental stakes are equally high. The Red Sea’s northern reefs are among the most pristine on the planet, home to dugongs, sea turtles, and rare fish species. Even careful construction risks damaging these habitats. Hybrid designs elevated sections over coral platforms and tunnels beneath shipping lanes are under review, though they add cost and complexity.

Political and Security Pressures

The Strait of Tiran is subject to international agreements, including Israel’s treaty-protected navigation rights under the Camp David Accords. Any disruption could spark political pushback. The region is already sensitive, with maritime security threats ranging from piracy to regional conflicts.

Long-term mega projects require stability. A leadership change in either country, shifts in foreign alliances, or rising regional tensions could stall or reshape the project. Similar ambitious proposals have failed before, such as the Bridge of the Horns between Djibouti and Yemen, which collapsed under the weight of political instability.

Lessons from the World’s Great Bridges

Studying other bridge projects offers valuable insight. The world’s most massive suspension bridges from the Great Belt Bridge in Denmark to the recently completed Canakkale 1915 Bridge in Turkey show how engineering ambition can succeed when funding, political will, and design innovation align.

Closer to home, the Gordie Howe International Bridge in Detroit-Windsor illustrates the patience required. Its construction began after decades of negotiations, and when finished, it will redefine cross-border logistics in North America.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, Cape Cod’s Bourne and Sagamore Bridges are reminders of what happens when maintenance lags. Built in the 1930s, they are now structurally deficient, causing traffic bottlenecks and raising safety concerns. For the Saudi–Egypt bridge, neglect decades down the road could undo its benefits, making long-term maintenance planning just as critical as the initial build.

Will the Red Sea Bridge Happen?

Funding appears to be in place, and technical groundwork is progressing. If groundbreaking happens within the next two years, a realistic opening could be around 2033. But every stage faces potential obstacles environmental lawsuits, regional disputes, cost overruns, or engineering setbacks.

The stakes are not just economic. This bridge would represent a statement of unity, ambition, and engineering mastery on a scale few nations ever attempt. Failure could be just as symbolic, leaving behind another unbuilt dream on the pages of feasibility reports.

A Continental Gamble Worth Watching

The Saudi–Egypt Red Sea Bridge is not just concrete and steel. It’s a test of vision, diplomacy, and resilience. If completed, it could rival the world’s most famous crossings and stand as a literal bridge between continents.

I’ve seen the Strait of Tiran’s waters shimmer under the desert sun, and I can imagine the shadow of a massive structure stretching across that expanse. Whether it becomes a landmark of global commerce or remains an unrealized ambition will depend on the ability of two nations to keep faith with a vision as challenging as the sea it must cross.