The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of RFK Stadium: Washington D.C.’s $3.8 Billion Gamble

RFK Stadium didn’t just host games it held memories. It echoed with cheers that once shook its concrete walls. Generations of fans stood shoulder to shoulder, watching legends fight for glory. But today, that iconic arena sits empty. What was once a proud symbol of Washington D.C. now crumbles beneath rust, silence, and time. And yet, out of this decay comes a bold and controversial proposal a $3.8 billion plan to tear down the ruins and build a smarter, more connected future.

I stood outside RFK recently and felt the weight of the past pressing through the rusted gates just like I did at the Dome at America’s Center. It didn’t feel abandoned. It felt paused, waiting for someone to care enough to press play again.

The Forgotten Dream That Built RFK

RFK Stadium began not with bricks, but with ambition. In the 1930s, civic leaders envisioned a monumental stadium to honor President Theodore Roosevelt. It was supposed to seat 100,000 and host global spectacles like the Olympics or presidential inaugurations. That dream fell apart under the weight of war, budget cuts, and political deadlock.

Instead, in 1958, Congress passed the DC Stadium Act, which finally brought progress. The new design was more practical: a 56,000-seat multi-purpose stadium on the eastern edge of Capitol Hill. Construction began in 1960, and the doors opened a year later. President John F. Kennedy threw the ceremonial first pitch, marking the start of a new era for sports in the nation’s capital.

A Golden Era Turns to Gray

RFK became a powerhouse almost overnight. The Washington Redskins (now the Commanders), Major League Baseball’s Washington Senators, and George Washington University’s football team all made it home. The venue’s unique design movable stands, intimate sightlines let fans feel close to the action in a way few other stadiums could.

But the early signs of trouble came quickly. The Senators never captured the city’s heart. Competing with the Baltimore Orioles, burdened with high rent, and plagued by poor performance, they couldn’t fill the seats. By 1971, after their final game drew just 14,000 fans, they left D.C. in chaos literally. Fans stormed the field, and baseball vanished for decades.

The Redskins, though, flourished. The 1970s and 80s were their golden years. Super Bowl titles. Packed stands. RFK became a fortress. Players talked about how the stands would sway when the fans roared. The energy was electric, and the entire city felt alive every Sunday.

But owner Jack Kent Cooke wanted more a modern stadium with full control and no political headaches. Years of disputes about the team’s name, environmental regulations, and city politics ended with a quiet exit. In 1996, the team moved to FedExField in Maryland. The lights dimmed. RFK, once unstoppable, began its decline.

Dying With Dignity or Refusing to Die

DC United gave RFK one last breath. From 1996 to 2017, the soccer club brought fierce passion and loyal fans. The drums, the chants, the smoke it wasn’t the NFL, but it was electric in its own way. In 2005, the Washington Nationals returned baseball to RFK temporarily. For a few years, fans dared to believe in a comeback.

But the structure was decaying. Paint peeled. Beams rusted. The facility couldn’t keep up with modern demands. By 2008, the Nationals had moved to Nationals Park. In 2017, DC United said goodbye too, heading to the sleek new Audi Field.

After that, RFK was a shell. A few college football games and military events passed through, but they were just echoes. By 2019, the city was spending millions every year just to maintain an empty relic. No revenue. No teams. No future.

Interior demolition began in January 2025. The stadium that once defined D.C.’s sports scene was being dismantled piece by piece.

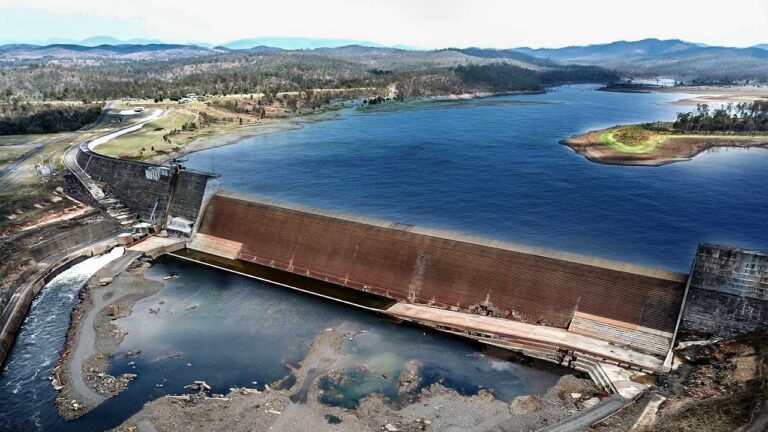

A New Vision: $3.8 Billion to Reclaim 170 Acres of History

Then came a bombshell. In April 2025, Mayor Muriel Bowser and the new Washington Commanders ownership announced a sweeping plan to not just replace RFK but to reimagine the entire 170-acre site.

At its core: a brand-new, 65,000-seat NFL stadium. But unlike the past, this stadium would reflect where sports and cities are going. It would host more than football. With a fixed roof and modern infrastructure, the space could support concerts, conventions, esports, and even year-round community events.

Natural light. Smart seating. Better acoustics. A design that brings fans closer to the field, physically and emotionally.

Beyond the Stadium: A City Within the City

The project splits the site into six districts three led by the Commanders, three by the city. It’s more than just a stadium. It’s a neighborhood reborn.

On the team’s side:

- A vibrant central plaza with restaurants, retail, and housing

- The stadium and its surrounding event spaces

- A waterfront zone with parks and performance venues

On the city’s side:

- 30 acres of preserved green space along the Anacostia River

- Renovated sports fields open to schools and community leagues

- A new Kingman Park development with affordable housing and family-focused spaces

In total, between 5,000 and 6,000 housing units will be built. At least 30% of them will be marked as affordable, targeting families and workers pushed out by rising costs.

The Commanders expect 1.4 million visitors a year at the new stadium. But fewer cars will come. Only 8,000 parking spaces are planned, compared to the 22,000 at FedExField. The city wants people to walk, bike, or use public transport. A new Metro station could even be considered based on future studies.

The Battle for Billions: Who Pays for All This?

The numbers are huge. The projected cost of $3.8 billion would make this one of the largest public-private projects in D.C.’s history.

Private investors, including the NFL and Commanders’ ownership group, will contribute around $2.7 billion. The remaining $1.1 billion would come from public funds.

Here’s how that breaks down:

- $500 million for roads, sewers, and utilities

- $22 million for transportation studies

- $181 million from Events DC for parking and other amenities

- $175 million in bonds issued by 2032

To cover these costs, the city wants to extend the “ballpark fee” a special tax created to fund Nationals Park. That tax was supposed to expire in 2026. Now it would continue under a new name: the “sports facility fee.” Businesses are already pushing back, arguing that D.C. is shifting the cost burden onto local commerce.

The Politics of Pride

Mayor Bowser sees this project as more than redevelopment. She frames it as a generational investment one that creates 16,000 construction jobs and 2,000 permanent positions. A magnet for events. A spark for neglected neighborhoods. A legacy for Washington, D.C.

And there’s another prize on the table: the Super Bowl. NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell has said the new stadium could make D.C. a serious contender. That means global attention, national prestige, and major tourism revenue.

But not everyone is convinced. Critics argue that taxpayer dollars should go to schools, healthcare, and public services not billionaire sports franchises. The mayor insists that the funding won’t touch the operating budget. Still, many residents are skeptical.

The final decision lies with the D.C. Council. As of now, council leadership has raised concerns about cost, equity, and long-term impact.

If the plan passes, construction could begin by late 2026. The stadium could open in time for the 2030 NFL season.

A City Reclaims Its Story

RFK Stadium’s story was never just about sports. It was about identity, belonging, and what a city chooses to preserve or leave behind. For decades, RFK stood as a symbol of pride and power in Washington, D.C. Then, it became a lesson in inertia. Now, through bold planning and public debate, it’s turning into something more a statement about the future.

What’s unfolding on the banks of the Anacostia isn’t just local renewal. It mirrors a global shift, where cities use sports infrastructure not just to host games, but to reclaim dignity, tell new stories, and reshape their place in the world.

Cities across the globe are doing the same reviving forgotten sites and using sports as a catalyst for national identity and transformation. After years of missed opportunities and setbacks, Morocco’s Hassan II Stadium isn’t just joining the global stage it’s aiming to define it. Co-hosting the 2030 FIFA World Cup marks the start of a larger vision, one driven by architecture, national pride, and the determination to shape how the world sees the country’s future.

Washington has that same chance. This project is more than construction. It’s about whether a city is ready to rise from its ruins, learn from its past, and build something that belongs to the people who never stopped believing in what it could be.